Pumpkin Cans: 2013

One nice thing about the revolution in micro breweries canning is that you get some interesting labels for different types of beers. Many micros will experiment with all sorts of different types of beers, and they'll often can them even if it's a seasonal release. And so we have this month's collection of cans---micro brewery cans for pumpkin beer & ale! I chose October to feature them because I collect the ones with a Halloween theme. I showed some of my Halloween-themed cans in 2009, so this month is a bit of a sequel: Halloween II: The Pumpkining!

|

|

Pumpkin Beer & Ale

Pumpkin Beer/Ale is not a style I remember seeing much until recently. I certainly can't remember any canned pumpkin brews before 2009 or so. But it's a popular seasonal style now.

How is it made? According to the Beer Advocate...

Often released as a fall seasonal, Pumpkin Ales are quite varied. Some brewers opt to add hand-cut pumpkins and drop them in the mash, while others use puree or pumpkin flavoring. These beers also tend to be spiced with pumpkin pie spices, like: ground ginger, nutmeg, cloves, cinnamon, and allspice. Pumpkin Ales are typically mild, with little to no bitterness, a malty backbone, with some spice often taking the lead. Many will contain a starchy, slightly thick-ish, mouthfeel too. In our opinion, best versions use real pumpkin, while roasting the pumpkin can also add tremendous depth of character for even better results, though both methods are time-consuming and tend to drive brewmasters insane.

Average alcohol by volume (abv) range: 4.0-7.0%

It's also a style that was common in the 17th and 18th centuries. Water supplies were often of uncertain safety, so various alcoholic drinks were popular. That included ales and ciders. Pumpkin ales were among the other types that the average farmer would have made. However, pumpkin ales were not particularly liked and were considered a drink for poor people who had few choices. When lager became popular in the mid-nineteenth century, such traditional ales faded from popularity.

But what about the imagery used on this month's featured cans. Some pumpkin beer cans (not shown here) just have a harvest theme. Where did the Halloween tied-in originate?

Jack O' Lanterns

Jack O' Lanterns were not originally associated with Halloween. They were related to Will o'the Wisps. In both cases they are names. "Jack of the Lantern" and "Will of the Wisp", a "wisp" being a bundle of stick or twigs which could be used as a torch. They're often trickster spirits that appeared as a ball of light that tried to lead men astray to their doom. In some stories, they're a ghost doomed to wander the Earth, unable to enter either Heaven or Hell. In one version, the ghost, named Stingy Jack, carries a glowing coal from Hell in a hollowed-out turnip to light his way as he wanders.

How did the Jack O' Lantern become so associated with Halloween? This is not the place for a long discussion of the assorted symbols associated with the pumpkin, but, indigenous to the Americas, it was one of the native crops quickly adopted by settlers, especially in New England. It provided food, drink (Pumpkin Ale!) and fodder for animals. Of course it became popular as pumpkin pie. As a fall crop the pumpkin was naturally associated with the harvest, nature, and fertility. Along with other gourds they were cheap and easy to grow, even on waste land or in middens (household garbage dumps). They also often did not take the familiar big round orange shape we associate with pumpkins now. They could be different shapes, and could be gray as easily as orange.

|

Joachim Beuckelaer, "The Country Market" (1566) art.com

In this painting by Flemish artist Joachim Beuckelaer, a group of peasants relax and show off their produce at a county market. There's a mixture of earthiness and sexuality clearly on display as well. The woman in the middle has her hand placed near some melons and gourds, just as her male partner's hand is poised on the edge of her breast. There's long been a psychological connection between sex and nature. In folklore, fertility in crops and human sexuality are inseparably intertwined and the pumpkin fit nicely into that role. It's no accident that Cinderella was transported in a carriage made from a magically transformed pumpkin (!) to meet her prince, a detail that was in traditional versions, and not just a Disney invention.

Nature has also been associated with danger. This is where the Jack O' Lantern comes in. In the early 19th century people (in the US at least) had begun to carve faces into pumpkins, a logical development from legends such as "Stingy Jack" and his coal in a hollowed out turnip. And, while not originally associated with Halloween, the timing was just right, as pumpkins were available just as Halloween rolled around. Kids could carve a scary face into a pumpkin thus making the danger inherent in nature obvious.

Halloween was already a time when people told and retold traditional folk tales as a way to deal with the fears of the unknown and the supernatural. Modifying an existing spirit, the Jack O' Lantern that tricked men into getting lost in the forest, the carved out pumpkin became the glowing, menacing face in the dark. As writer Terry Pratchett put it in Hogfather, “Old gods do new jobs.”

In the mid and late 19th century Halloween and the Jack O' Lantern were affected by the changing nature of the family. Children were no longer seen as just tiny adults and the family began to center more on raising children as a process of development. This domestication modified Christmas, which evolved from a somewhat disreputable holiday with too much partying and drinking, into a family and child-centered gathering at home.

Halloween and the carved pumpkin underwent a similar process, although a holiday based upon entertaining fear exemplified by a mischievous grinning spirit was not quite as easily tamed as Christmas's St. Nick. Halloween developed a dual nature, partly a time for wholesome activity and partly a time for scares and tricks, sometimes called "Devil's Night." Reflecting that duality, Jack O' Lanterns could be either happy or silly on the one hand, or threatening and scary on the other. This is reflected in the Pumpkin cans (below) which may have either scary and friendly pumpkin faces.

|

|

The plain pumpkin itself changed meaning as well. As industrialization remade American society, rural life became romanticized. An urban population looked to older crops such as the pumpkin and "Indian Corn" as symbols not of the dangers of nature, but of a society now lost. Farm stands along country roads began to sell pumpkins not as food items, but as decorations for homes in cities and suburbs. The vegetable that fed early settlers and their livestock became surbanized.

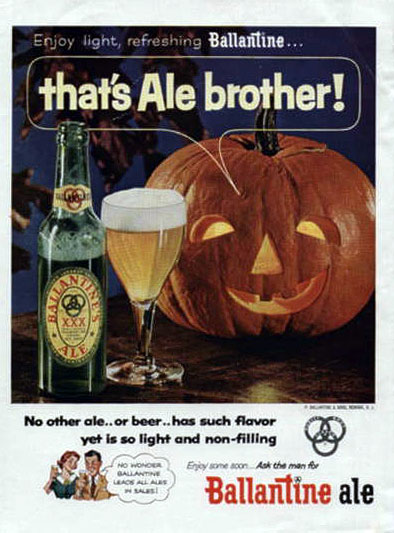

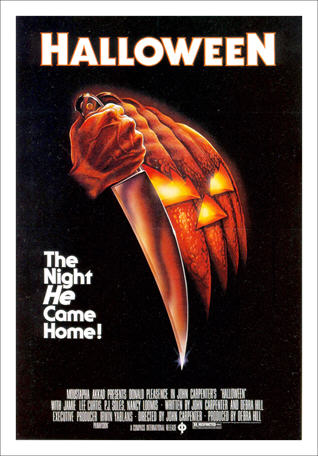

By the middle of the 20th century Halloween was associated with kids trick-or-treating and the tamed, happy Jack O' Lantern was common. (see the Ballantine Beer ad below) But the roots of the Jack O' Lantern in ancients fears of nature never left. Scary Jack O' Lanterns continued to appear on front porches every October 31. In 1978 the poster for the movie Halloween featured a slashing knife and a threatening Jack O' Lantern with fangs matching the stabbing knife. Scary movies, just like the Jack O' Lantern itself, are a way to neutralize fear by controlling it. The person carving the face (the mask) into the pumpkin, controls whether it's silly, friendly, or scary. And the movies, like Halloween, are a way of boxing fear into a limited space. Like scary stories, the fear is caged within the limits of a finite narrative.

|

|

Happy Pumpkin. 1955. |

Halloween, 1978. |

Halloween's killer, Michael Myers, wears a mask just as the face of the Jack O' Lantern itself can be understood as a mask. Posters for sequels to Halloween made Myers' face orange, turning it into a burlesque of a Jack O' Lantern, the mask on the killer echoing the impersonal "face' of the Halloween pumpkin. Michael Myers is also, like his movie cousin Jason Voorhees from Friday the 13th, unstoppable, as if they were a force of nature preying on the unsuspecting, just like the original Jack O' Lantern as trickster spirit.

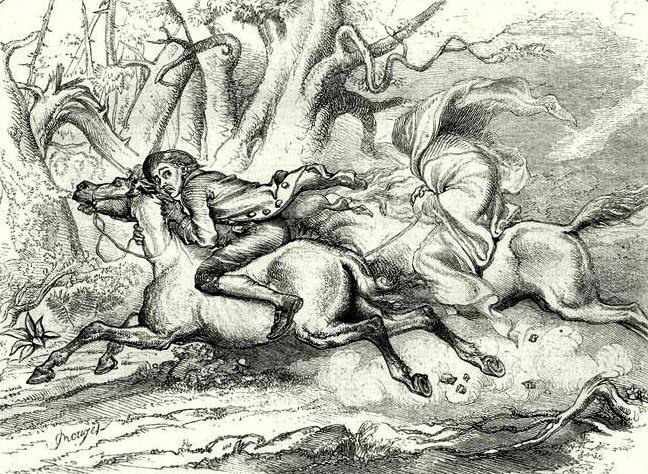

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow

"The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" (1820) is a popular Halloween-time story, almost two centuries after it was written. The cool Shipyard can shown here has the popular version of the Headless Horseman holding a flaming Jack O' Lantern. This popularity of this version can be largely attributed to Disney's "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" released as a short film in 1958. (It was originally part of a longer movie released in 1948). There were versions filmed previously (including a 1922 version with Will Rogers as Ichabod Crane!) and many since. But Disney's version, shown repeatedly at Halloween on TV, helped cement the image in peoples' minds.

|

In the original 1820 version by Washington Irving the Horseman threw a pumpkin at poor schoolmaster Crane, but it was not a flaming Jack O' Lantern. You can compare the two versions below. At left is an 1849 version by F.O.C. Darley. At right is a screen capture of the Horseman from the Disney version. (Both may be clicked to see a larger version) Actually I think the 1849 version is a lot scarier. Moreover, the 1948 Disney version was, as you'd expect from Disney, kid-friendly, with Crane and his horse being comic figures, acting as scared cartoon characters do, shivering and grabbing hold of one another in fright.

|

|

Here is how the Horseman and his encounter with Schoolmaster Ichabod Crane are described in Washington Irving's original tale. Crane has been listening to local ghost-stories, including several about a spectral horseman. As he rides home from a party Crane and Gunpowder (Crane's old, half-blind horse) alike are becoming increasingly spooked by the nighttime sounds and shadows of the woods through which they are traveling. But Crane senses that he is not alone.

Though the night was dark and dismal, yet the form of the unknown might now in some degree be ascertained. He appeared to be a horseman of large dimensions, and mounted on a black horse of powerful frame. He made no offer of molestation or sociability, but kept aloof on one side of the road, jogging along on the blind side of old Gunpowder, who had now got over his fright and waywardness.

Ichabod, who had no relish for this strange midnight companion, and bethought himself of the adventure of Brom Bones with the Galloping Hessian, now quickened his steed in hopes of leaving him behind. The stranger, however, quickened his horse to an equal pace. Ichabod pulled up, and fell into a walk, thinking to lag behind,—the other did the same. His heart began to sink within him; he endeavored to resume his psalm tune, but his parched tongue clove to the roof of his mouth, and he could not utter a stave. There was something in the moody and dogged silence of this pertinacious companion that was mysterious and appalling. It was soon fearfully accounted for. On mounting a rising ground, which brought the figure of his fellow-traveller in relief against the sky, gigantic in height, and muffled in a cloak, Ichabod was horror-struck on perceiving that he was headless!—but his horror was still more increased on observing that the head, which should have rested on his shoulders, was carried before him on the pommel of his saddle! His terror rose to desperation; he rained a shower of kicks and blows upon Gunpowder, hoping by a sudden movement to give his companion the slip; but the spectre started full jump with him. Away, then, they dashed through thick and thin; stones flying and sparks flashing at every bound. Ichabod's flimsy garments fluttered in the air, as he stretched his long lank body away over his horse's head, in the eagerness of his flight.

They had now reached the road which turns off to Sleepy Hollow; but Gunpowder, who seemed possessed with a demon, instead of keeping up it, made an opposite turn, and plunged headlong downhill to the left. This road leads through a sandy hollow shaded by trees for about a quarter of a mile, where it crosses the bridge famous in goblin story; and just beyond swells the green knoll on which stands the whitewashed church.

As yet the panic of the steed had given his unskillful rider an apparent advantage in the chase, but just as he had got half way through the hollow, the girths of the saddle gave way, and he felt it slipping from under him. He seized it by the pommel, and endeavored to hold it firm, but in vain; and had just time to save himself by clasping old Gunpowder round the neck, when the saddle fell to the earth, and he heard it trampled under foot by his pursuer. For a moment the terror of Hans Van Ripper's wrath passed across his mind,—for it was his Sunday saddle; but this was no time for petty fears; the goblin was hard on his haunches; and (unskillful rider that he was!) he had much ado to maintain his seat; sometimes slipping on one side, sometimes on another, and sometimes jolted on the high ridge of his horse's backbone, with a violence that he verily feared would cleave him asunder.

An opening in the trees now cheered him with the hopes that the church bridge was at hand. The wavering reflection of a silver star in the bosom of the brook told him that he was not mistaken. He saw the walls of the church dimly glaring under the trees beyond. He recollected the place where Brom Bones's ghostly competitor had disappeared. "If I can but reach that bridge," thought Ichabod, "I am safe." Just then he heard the black steed panting and blowing close behind him; he even fancied that he felt his hot breath. Another convulsive kick in the ribs, and old Gunpowder sprang upon the bridge; he thundered over the resounding planks; he gained the opposite side; and now Ichabod cast a look behind to see if his pursuer should vanish, according to rule, in a flash of fire and brimstone. Just then he saw the goblin rising in his stirrups, and in the very act of hurling his head at him. Ichabod endeavored to dodge the horrible missile, but too late. It encountered his cranium with a tremendous crash,—he was tumbled headlong into the dust, and Gunpowder, the black steed, and the goblin rider, passed by like a whirlwind.

The next morning the old horse was found without his saddle, and with the bridle under his feet, soberly cropping the grass at his master's gate. Ichabod did not make his appearance at breakfast; dinner-hour came, but no Ichabod. The boys assembled at the schoolhouse, and strolled idly about the banks of the brook; but no schoolmaster. Hans Van Ripper now began to feel some uneasiness about the fate of poor Ichabod, and his saddle. An inquiry was set on foot, and after diligent investigation they came upon his traces. In one part of the road leading to the church was found the saddle trampled in the dirt; the tracks of horses' hoofs deeply dented in the road, and evidently at furious speed, were traced to the bridge, beyond which, on the bank of a broad part of the brook, where the water ran deep and black, was found the hat of the unfortunate Ichabod, and close beside it a shattered pumpkin.

Despite being missing from Irving's original version, the Jack O' Lantern head was just too good an addition for it not to catch on. Reflecting the popularity of the story, Tarrytown, New York, where the original story took place, renamed itself Sleepy Hollow and there is a statue in town showing Crane being chased by the Headless Horseman, and yes, he's carrying a Jack O' Lantern head.

Note that the Shipyard can reads "It comes alive once a year." In Irving's story the Horseman appeared at random times. There was no particular connection to Halloween. But it's common in folklore for apparitions to appear on a specific anniversary, so it's not surprising that a tale that has become associated with Halloween would also add that aspect to the story.

Want to see more of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow?

The Disney version (on Youtube)

The original by Washington Irving (on Gutenberg.org)

Halloween Now

Halloween still maintains its multifaceted nature. It's a child's holiday, although trick-or-treating has often moved into the safe, controlled space of the shopping mall and off of neighborhood streets. Pumpkin Patches are advertised as safe, family-friendly places to visit on a fall afternoon.

At the same time, a more sexualized adult version has emerged over the past couple of decades, with Halloween as a time for adults to dress up and play. It's a time for sexy costumes and drinking at parties with other adults, a return to the holiday's roots as a harvest-time festival. A sexualized Halloween then has taken on the aspects of carnival, a time of indulgences in vice before a season of want, in Halloween's case, the start of Winter rather than Lent.

|

|

| Two competing visions of the Halloween pumpkin. | (Costume from eBay) |

There is also still a sense of danger. Some religious fundamentalists complain that Halloween has "Satanic" roots. Stories about razors in candy scare parents, and television shows horror movies and shows featuring monsters, aliens and ghosts.

In this context lets look at the crop of Halloween Pumpkin cans below.

2013's Halloween Jack O' Lantern Cans

Here are the new micro cans that I have found so far with a Halloween Jack O' Lantern theme (defined rather loosely). Next to each one I added a few notes relating it to the previous discussion of Halloween and Jack O' Lanterns There is also a link to the brewers' sites. (links each open a new window)

|

The happy Jack O' Lantern as child in a pumpkin patch theme is non-threatening. The ale's name itself, "Pumple Drumkin" sounds childish. Even the shade of orange seems somehow milder than that used on the other cans here. It almost looks like a soda can. It's Halloween as a child-friendly family holiday. |

|

This is Wild Onion's second (I think) Pumpkin Ale can. This Jack O' Lantern is clearly threatening with its facial expression as well as the spikes below and the spider web. The full beer glass emphasizes that this is a product for adults. This is Halloween as a dangerous diversion. |

|

The image from "Sleepy Hollow" is on the scary side of the scale, as is the face on the Jack O' Lantern. But the way the glass of beer is raised is more celebratory than threatening. It looks as if he's toasting his yearly appearance and inviting the viewer to join him. It's Halloween as celebration. |

|

A happy but not childish Jack O' Lantern. It has a slight lear and is winking at the viewer. That places this Jack O' Lantern as part of the modern, sexualized adult Halloween, a message emphasized by the "We Love Beer" at the top. |

|

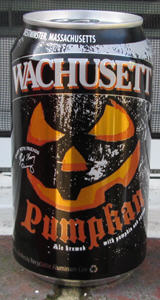

Another "spooky" as opposed to "happy" or "silly" pumpkin. The font choice and the orange on black add to the somewhat sinister expression on the pumpkin. Pumpkan | Wachusett Brewing Company

|

|

A UFO pumpkin? Nice eye-catching orange label. Not spooky, but scifi themes are popular on Halloween too. From Harpoon Brewery in Boston, Massachusetts.

|

|

Andersonville uses a horned bear on their labels. The Halloween part is the orange background and the cool little bats. They must have a wide distribution because I found this one in a market in Falls Church, Virginia. From Anderson Valley Brewing Company in Boonville, California.

Anderson Valley Brewing Website.

|

|

Not a Halloween theme, but some nice autumn pumpkins from Four Peaks Brewing Company in Tempe, Arizona.

|

See all of my Halloween Can Pages

Budweiser Halloween Aluminum Bottles

Sources Used

Beer Advocate Pumpkin Ale

Morton, Lisa. Trick or Treat: A History of Halloween (2012)

Ott, Cindy. Pumpkin: The Curious History of an American Icon (2012)

Wikipedia, "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow"

I could not have written this page without the insights provided by Professor Cindy Ott. Check out her site on the history of pumpkins as icon.

Of course, any errors in interpretation are mine alone.