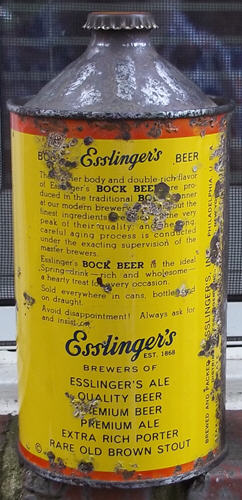

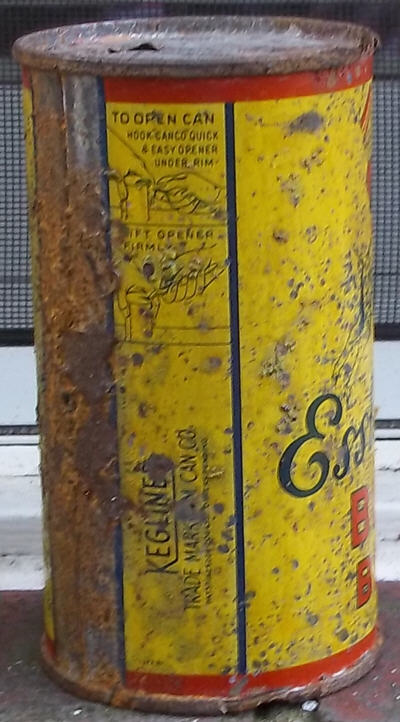

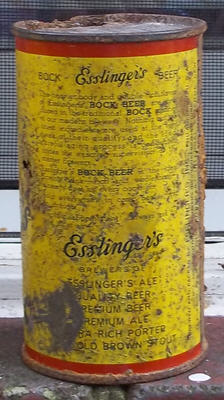

Esslinger Bock Cans, circa 1930s

|

|

|

This month I am showing a few favorite cans from Philadelphia's Esslinger Brewing Company. I especially like this label because it combines the traditional Bock Beer goat with the little waiter/bellhop figure that Esslinger long used as a mascot. The date code on the quart pictured above is for 1941. The code for the flat top pictured below is from 1938. Interestingly, before World War II Esslinger put recipes on the backs of their cans for dishes such as Welsh Rarebit that used Esslinger's Beer. The two bock cans pictured here do not have recipes, but a plug for their bock and other beers.

|

|

|

Bock beer is a dark, heavier beer and usually has a higher alcoholic content than most lagers or ales. Traditionally, it was brewed in the winter and sold in spring. In the 1930s and 1940s breweries in a particular region would organize a "Bock Beer Day" (usually around March 20) and each would start selling their Bock Beer on that day. Occasionally breweries would violate the agreement to get a jump on their competitors, but for the most part the breweries stuck to the arrangement and have a small celebration. Bock Beer is traditionally represented by a goat (see below for more on why) and the celebration would include a contest to pick the official Bock Beer goat for that city or region for that year.

Bock beer was not universally popular across the entire US. It was most popular in what is called the "bock belt" which roughly stretched from Washington, D.C., north through Pennsylvania and into New York state. There are bock beer cans from other regions of the country, including Michigan, California, and Richmond, Virginia, but most bock beer was canned in the "bock belt." The Valley Forge can featured for August 2005 came from the center of this area and the regional popularity of this darker beer in the region no doubt explains why Scheidt regularly produced it.

Bock Beer = Goats?

M![]() any bock beer cans have the image of a goat on them. I've heard that this was because bock beer is brewed in January, during Capricorn, but the reality is probably simpler. Bock means "goat" in German. Supposedly bock beer was created centuries ago in Einbeck Germany. The darker, heavier beer they made in winter became known as "Einbeck Bier", which turned into "Ein (or "one") Beck bier" which then turned into "Ein BOCK bier." And since "BOCK" means "GOAT" the rest is history.

any bock beer cans have the image of a goat on them. I've heard that this was because bock beer is brewed in January, during Capricorn, but the reality is probably simpler. Bock means "goat" in German. Supposedly bock beer was created centuries ago in Einbeck Germany. The darker, heavier beer they made in winter became known as "Einbeck Bier", which turned into "Ein (or "one") Beck bier" which then turned into "Ein BOCK bier." And since "BOCK" means "GOAT" the rest is history.

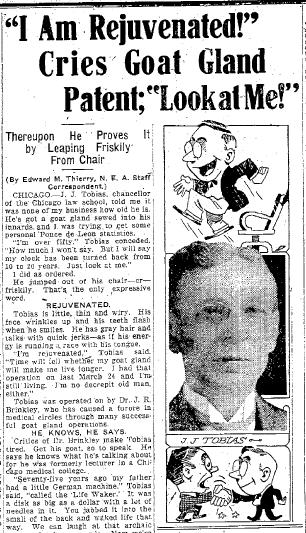

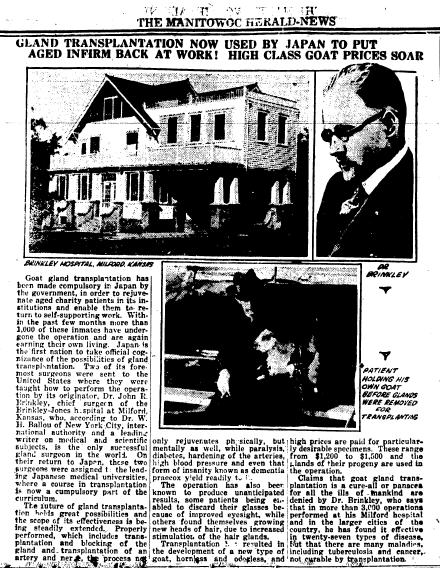

There is also an additional meaning attached to spring and sex. Spring is associated with love and a renewal of sexual interest ("A young man's thoughts turn to..." etc. etc.) Similarly, goats, male goats at least, are associated with male sexual prowess. For example, the term "horny old goat" refers to an older male who is still interested in sex beyond an age at which society is confortable with such interest. A popular quack medicinal treatment for male impotence in the 1920s was transplanting goat testes into a human patient. Quack doctor John Brinkley (link opens new window) made a fortune promoting this "treatment." (Kansas Memory has an online version of one of Brinkley's pamphlets, this link also opens a new window) Conjoining goats and springtime with sexual significance then makes some sense. Of course it has also long been popular to sell alcoholic beverages by using sexual imagery as well, most notably with the simple use of pretty girls in beer ads, a tradition that long, long predates modern advertising.

Below I've included a couple of news stories about Brinkley's goat gland treatment. I especially like the photo of the patient with "his" goat below. Patients at Brinkley's hospital could pick the goat they wanted the surgeon to use from a pen of goats, much like restaurant goers can pick "their lobster" from a tank in a restaurant. I could go off on a tangent here about the common use of lobsters and pretty girls in pre-prohibition liquor and beer ads, but I will write about that advertising oddity at another time.

|

|

| From the Ogden Standard-Examiner, Utah, September 3, 1020, p. 12. | From the Manitowoc Herald News, Wisconsin, March 13, 1923, p. 8. |