In 2005 I wrote the Woodrow Wilson House's exhibit, “No Temperance in It': Woodrow Wilson, the Prohibition Amendment and Brewing in Washington, D.C." The exhibit ran from October 27, 2005 until April 10, 2006. As part of my research I wrote a short history of the passage of the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act which I present here in the hopes that it may be useful. I also wrote a page on the history of Prohibition in Virginia. As always, corrections and additions are welcome, please email me at Mark@rustycans.com

“No temperance in it…”: Woodrow Wilson & Prohibition

Because Prohibition began in Wilson’s administration it is often assumed that he supported it. In fact, Wilson vetoed the infamous Volstead Act which enforced Prohibition and he opposed a federal law enforcing what he thought was a personal moral issue. However, after the 18th Amendment passed and it became law he defended its enforcement. Neither a "dry" or a "wet" what Wilson supported was a middle position, sometimes referred to as “temperance” where he supported laws encouraging moderation rather than a full banning of alcoholic beverages. Wilson was himself a moderate drinker. His home had a small wine cellar and he occasionally enjoyed a glass of good Scotch in the evening, although he seems to have never drunk to excess.

Wilson's position of moderation was sometimes called "temperance" or "true temperance," but this can be a bit confusing because many of the groups that supported full prohibition called themselves "temperance" groups. For the purposes of this essay “prohibition” will refer to the total banning of alcoholic beverages for consumption, while “temperance” will refer to restricting alcoholic beverages in order to limit their use while allowing at least some such beverages (usually low alcohol beer and wine) to remain legal. Likewise the term “wet” or “wets” will refer to those who opposed prohibition while “dry” or “drys” were those who supported prohibition.

Furthermore, there sometime appears some confusion over the difference between the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act. The two are not the same, but were each separate parts that together made up Prohibition. The 18th Amendment established the Prohibition of "intoxicating" (alcoholic) beverages in the US, but the Volstead Act was necessary to define what the amendment meant by “intoxicating” and it gave the government the legal right to enforce the law. Without the Volstead Act, the 18th amendment had no teeth, and without the 18th amendment the Volstead Act was unnecessary.

The 19th Century

Temperance movements have a long history in the United States, dating to the early 19th century when drinking hard liquor--and alcoholism--were much more prevalent than in the early 21st Century. According to some estimates the average American drank three times more alcohol in the 1790s than they did in the 1990s. (That is measuring the actual alcohol contained in the beverages consumed) At first, most temperance movements aimed at moderation rather than total abstinence. They were designed to combat prolonged drunkenness, not total abolition of all alcoholic beverages. However, those supporting abolition of alcoholic beverages eventually drowned out the voices for moderation.

In 1851 Maine became the first state to totally go “dry”, banning the sale of alcohol except for ''medicinal, mechanical or manufacturing purposes.'' Prohibition laws are still sometimes referred to as “Maine Laws” for this reason. By 1855, twelve states had adopted total prohibition. The Civil War stopped the movement towards prohibition, however, as did the difficulties in enforcing it. Most of the “dry” states rejoined the “wet” ranks by 1880, with Maine being the notable holdout, although even it had riots over alcohol.

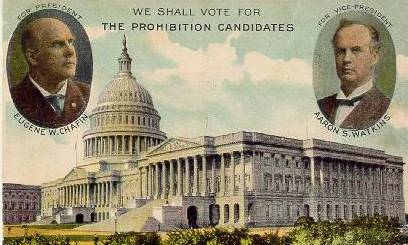

After the Civil War several Prohibitionist groups were formed that would dominate the campaign to ban alcohol over the next several decades. In 1867 the Prohibition Party was formed to run its own candidates for public office. The Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was formed in 1873 in Ohio. The two groups followed different strategies. The Prohibition Party believed that the only way to establish Prohibition was to elect candidates running primarily as Prohibitionists. The WCTU would support any candidate, Republican or Democrat, that promised to support their agenda.The Anti-Saloon League (ASL) was founded in 1895 and followed the WCTU model supporting “dry” candidates regardless of party. The two groups also worked to pass prohibition laws piecemeal, making first towns and then counties dry through local referendums. Eventually entire states could be made "dry" this way. It was a successful strategy. By 1918, twenty-seven of the forty-eight states were already officially ‘dry” as were the District of Columbia and Alaska.

1912 Prohibition Party postcard.

The 1916 Election

The 1916 election was a watershed moment for the prohibition campaign. Both Democratic incumbent Woodrow Wilson and Republican candidate Charles Evans Hughes ignored the Prohibition issue, as did both party's political platforms. Both parties were split. Both had strong wet and dry factions and with the election expected to be close, neither candidate wanted to alienate part of their base.

Dry organizations--including the WCTU and ASL--followed a two-path strategy. They worked to be certain that neither Presidential candidate dared move too close to "wet" candidates and they worked to elect dry candidates to Congress. Their efforts were successful to a degree that surprised drys and wets alike. The Republicans made large gains in Congress and added 65 new drys to the House. The Democrats lost seats, barely maintaining control of Congress. However, even though they sent fewer members to the House, the Democrats still added 20 new dry members. When the 65th Congress met in 1917 the Democratic drys outnumbered their party's wets by 140 to 64 while dry Republicans outnumbered their wets by 138 to 62. For the first time a new Congress would be dominated by prohibition supporters.

Wilson was also put in a difficult spot. Both parties were split between wets and drys, but 17 of the 30 states Wilson carried in 1916 were dry while Hughes only carried 6 of the 23 dry states (along with 12 of the 25 wet). So while both parties were split, Wilson knew that the dry states had carried him to reelection, something that was made explicit to him immediately after the election by on of his progressive supporters, writer John Palmer Gavit, who wrote to Wilson that he should not forget that he had “been elected by the vote of ‘dry’ states.” (Gavit to Wilson, November 22, 1916, Papers of Woodrow Wilson 40:42. Hereafter PWW followed by volume number and page number.)

Candidate Wet States Carried Dry States Carried

Wilson 13 17 Hughes 12 6 Total 25 23 The election results had emboldened the dry members and disheartened the wets. Soon after the election Purley Baker, head of the ASL, issued a statement noting that “…the political party that is not willing to put a plank in its platform, and the candidate, from the President down, who is not willing to stand squarely on that plank, are not worthy [of] support by patriotic American citizens.” (Kerr, 194) Given that such a stance would alienate the sizable wet voting bloc, both parties were caught in a dilemma. No matter what stance they took, it would alienate part of their base. Looking for a way out Congress decided to pass the issue to the states by passing the dry's desired Amendment to the Constitution establishing national prohibition. It would then be out of Washington’s hands.

The Sheppard Act

Before the new 65th Congress could even meet, the lame duck 64th Congress started the movement by passing dry legislation. When the 64th Congress met for a final time at the end of 1916 it began consideration of a number of prohibition laws. The first measure to pass was the Sheppard Act, named after dry Senator John Morris Sheppard of Texas. The Sheppard Act made Washington, D.C. totally dry. The bill’s sponsors, however, had to dodge an institutional roadblock, the House District of Columbia Committee. The committee, chaired by Ben Johnson (D-KY) had killed earlier attempts to enact Prohibition in DC by simply refusing to meet. By submitting the bill to the Senate first, drys hoped to bypass the House committee.

The wets tried to derail the law by asking for a referendum to allow the citizens of DC to vote for or against Prohibition. Congress refused to allow such a referendum and Wilson, correctly, noted that there was no mechanism for such a vote. As he told a reporter…”there is no voting machinery in the District of Columbia. It would have to be created. There are some practical difficulties about it.” (Wilson Press Conference, 15 January 1917, PWW 50:771). However, the resolution calling for a District referendum died in the Senate with a tie vote. (see chart below) Vice-President Thomas Marshall did not cast a deciding vote, so the amendment failed.

The Senate vote for the Referendum (a yes vote supports a referendum on the Sheppard Act within the District)

9 January 1916

Vote Democrats Republicans Total YES 26 17 43 NO 23 20 43 The wets then tried to delay passage by calling for a roll call ten different times. The drys continued their efforts however, and the bill finally passed. (see next chart)

The Sheppard Act Vote in the Senate

9 January 1916.

Vote Democrats Republicans Total YES 28 27 55 NO 22 10 32 Once the bill passed wets began lobbying Wilson to veto the law. Wilson political ally, American Federation of Labor (AF of L) President Samuel Gompers visited Wilson and pressed him to kill the bill noting that beer was the working man’s beverage. Banning it would discriminate against workers while allowing the wealthy to keep their stocks of hard liquor. Gompers had a legitimate point. Beer and ale are relatively inexpensive, but will only last a short while in storage, while more expensive distilled liquors will last for years. Caught between the two factions, drys and wets, Wilson told his Secretary, Joseph Tumulty, “how impossible this is for me, especially at [the] present.” However, on March 3, 1917 Wilson signed the bill.

Why did Wilson sign the Sheppard Act? As he noted at the time, the Constitution gives Congress police power for the District, so the law fell within Congress’s responsibility. Historically, for this reason, Presidents rarely interfered with Congress when it came to governing the District and Wilson was no doubt aware of the precedent. However, the growing political strength of the drys also probably played a part. Wilson was very aware of his role as the head of the Democratic Party, and vetoing the Sheppard Act would have split the party at a crucial time.

Wilson needed to save his political capital for other battles in Congress. The US would enter the First World War in early April of 1917 and Wilson had spent the winter of 1916-1917 dealing with the European war and trying to get Congress to pass legislation arming US merchant ships against German submarines. Then on January 31, 1917, Germany has announced that they would begin unrestricted submarine warfare. On February 3 the US broke diplomatic relations with Berlin. The House of Representatives approved arming US ships, but the Senate balked, frustrating Wilson's efforts. In light of this growing international and political crisis, prohibition in the District was best pushed to one side. Wilson could not risk alienating members of Congress over a local issue when he might need their votes for defense bills.

Disappointed wets did not give up however, and seven saloon-keepers filed suit with the District Supreme Court. The plaintiffs claimed that by selling them licenses the District government had recognized the saloon-keepers’ right to sell liquor and therefore the Sheppard Act violated their property rights. The District Judge, Justice Gould, refused the claim noting that the internal revenue license was in fact a tax not a license, and did not guarantee the right to sell intoxicants. He noted that the US Supreme Court had earlier ruled there was no over-riding legal right to sell liquor because there were important public health and safety rights which took precedence over property rights. (“Sheppard Dry Law is Upheld by Court” Washington Star, 24 October 1917).

DC Goes Dry

At midnight 31 October 1917, Washington, D.C. went dry without a great deal of fanfare. Many restaurants had already run out of liquor and were serving ice water. Private clubs had sold their remaining stock to their members as private stocks of liquor were still legal.

A few areas in the city were crowded that final evening. Ninth street from Pennsylvania to K Street, which included Washington’s tiny Chinatown, was crowded until after 1 am with people celebrating, or mourning, the end of John Barleycorn at DC’s Chinese restaurants. M Street between Rock Creek and the Aqueduct Bridge, a saloon-heavy area, ended up closing before midnight as stocks were exhausted. The same was true along H Street NW, another area populated by saloons. (“King Booze Quits Throne in Capital” Evening Star, 1 November 1917).

A local DC photography studio made a mock-up coffin for whiskey which became a popular prop for doughboys getting their pictures taken in their new uniforms. The top of the coffin prop reads "Gone But Not Forgotten." (Photo courtesy of Wes P. Thanks Wes!)

DC's Breweries

There were still four breweries operating in DC in 1917, all of which were forced to close. Washington Brewing Company simply shut its doors. National Capital Brewing switched to making Carry's Ice Cream. They later sold the ice cream business but kept the family’s other concern, a local bank.

Christian Heurich’s brewery was the largest in Washington. They tried switching to a non-alcoholic fruit drink. Heurich was 75 years old in 1917 and had invested much of his fortune in real estate so he was safe financially so he could easily have retired. However, he did not want to just fire all of his workers simply because Congress decided that the people in DC could no longer buy alcohol. So in September 1917, Heurich bought $100,000 worth of apples. He stored them in his lagering cellars, made them into a mash, pasteurized it so it would not ferment, and produced a sparkling apple drink. He added hops to the resulting drink for flavor and stored it in empty beer kegs that had been sterilized. The drink went over well, but the remaining stock soon began to ferment despite the pasteurization, probably because of lingering yeast in the kegs. Heurich hurriedly sold off as much of the stock as he could while it was still legal to do so. According to Heurich’s unpublished memoirs, a limo from the White House came to the brewery to buy some a keg or two. The remaining unsold two thirds of the apple drink was put into storage. Once Prohibition was lifted in 1933 and Heurich's reopened, it was poured down the drain to make room for real beer.

The Lever Bill

The Sheppard Act was not the last prohibition measure passed in 1917. Wilson had tried to avoid alienating both wets and drys by claiming that prohibition was a “social and moral” issue, and therefore not properly part of a party platform. However when the US declared war on Germany on 6 April 1917, such "social and moral” issues suddenly became a politically legitimate topic for Congress. The brewing industry in particular became a target because it was dominated by German immigrants and first generation German-Americans. The prohibitionists made the most of this by tying German brewers as much as possible to the nation of Germany with which the US was at war. At times this campaign reached ridiculous levels, such as when rumors spread through Washington, D.C. that local brewer Christian Heurich had installed cannon on his Maryland dairy farm overlooking the capitol. One dry magazine, American Issue made the connection between alcohol and the war explicit noting, “German brewers in this country have rendered thousands of men inefficient and are thus crippling the Republic in its war on Prussian militarism….” (American Issue, 3 August 1917)

The alcoholic beverage industry also vulnerable because it consumed grain that could be used for food and coal that could be used for factories turning out war material. Moreover, intoxicating beverages were blamed for lowering worker productivity at a time when the nation needed an industrial push to provide weapons for the US and the allies both. The drys exploited this vulnerability as Washington moved to regulate American industry to make war production more efficient. In anticipation of this need, Congress in 1916 had formed the Council of National Defense. Its members were the Secretaries of War, the Navy, Interior, Agriculture, Commerce, and Labor. Secretary of War Newton Baker acted as the Chair. The Council was formally established on 29 August 1916 and its responsibilities included coordinating transportation, industrial and farm production, financial support for the war, and public morale.

One of the experts hired by the Council was Professor Irving Fisher of Yale. Fisher was an economist, an active support of eugenics (and, incidentally, the inventor of the rolodex), and a firm believer in the dangerous effects of drinking alcohol. Fisher prepared a report claiming that if brewers were forbidden from using barley, the resulting savings in grain could produce “eleven million loaves of bread a day.” Fisher formed a Committee on War Prohibition and began campaigning for dry laws nationwide. As the pro-prohibition magazine The Independent, noted, “…shall the many have food or the few have drink?” (May 26, 1917) As an economist Fisher was interested in the financial costs of alcohol. In the 1920s he put specific numbers to the same costs of alcohol he was warning of in 1917…

Since scientific research has shown that alcoholic beverages slow down the human machine, and since the human machine is the most important machine in industry, we should expect the use of alcoholic beverages to slow down industry, and we should expect prohibition, if enforced to speed up industry. Experiments show that two or four glasses of beer a day will impair the work done in typesetting by 8 percent, increase the time required for heavy mountain marches 22 per cent, and impair accuracy of shooting under severe Army tests 30 per cent….”Fisher then went on to calculate that “the productivity of labor would be increased from 10 to 20 per cent by effective prohibition.” (Irving Fisher, 1926A, Works, VIII, p. 127)

While Fisher’s calculations were made a decade after the war, the argument that alcohol hurt productivity had long been made by dry advocates. It was countered by labor supporters such as Samuel Gompers, who argued that beer was a working man’s beverage and that banning it would amount to discrimination on the basis of class because the wealthy would still be able to keep their private stocks of hard liquors. Both arguments seemed to resonate with Wilson as he searched for a compromise that might satisfy both sides, stopping the “waste” of grain used in making alcohol, while not penalizing workers by banning their (inexpensive) beverage of choice.

In June 1917 the House considered the Lever Food Control Bill, which would allow the government to regulate food production in the US in order to guarantee the most effective use during the war. Drys seized on the opportunity to enact Prohibition as a conversation measure. Congressman Alvin Barkley of Kentucky (later President Harry Truman’s Vice-President) moved to amend the bill so as to forbid the use of foodstuffs in making alcohol. After three attempts his amendment passed. Wets immediately threatened to hold up the bill until the dry measures were stricken from it. (Peter Odegard, Pressure Politics: the Story of the Anti-Saloon League, 1928, 166-167.)

In response Wilson asked the Anti-Saloon League to withdraw the Barkley Amendment at least as it affected the making of light beers and wine. League President James Cannon agreed, providing Wilson wrote a public letter requesting that the League do so. Wilson hesitated, but faced with the defeat of a bill he felt was necessary to the war effort, he agreed. His letter stated,

I regard the immediate passage of this bill as of vital consequence to the defense and safety of the nation. Time is of the essence, and yet it has become evident that heated and protracted debate will delay the passage of the bill indefinitely if the provisions affecting the manufacture of beer and wine are insisted upon.” (PWW 29 June 1917 43:42)

Cannon replied

“We are aware of the threats [to the Lever Bill] made by the friends of beer and wine in the Senate….We beg to assure you that as patriotic American….we will not for our constituency offer any obstruction to the prompt passage of the food bill.” (PWW 30 June 1917 43:64)

Some drys regarded this compromise as a defeat. Senator James Vardaman of Mississippi complained that “the good old ship prohibition…was submarined day before yesterday by the President of the United States. It is now lying on the bottom beneath about forty fathoms of beer and wine.” The wets saw it as a warning that the drys had gained enough legislative power that it took the direct, open intervention of the President to counter their influence. The Cincinnati Enquirer complained that “…we have the President of the United States under orders to an officious and offensive lobby.” (Odegard 170-171)

After the release of Wilson’s letter the food bill passed Congress on August 10. It prohibited the use of foodstuffs (i.e. grain) in distilling, cut back on the amount of grain and coal available to brewers, and allowed Wilson to ban the making of beer and wine in the future if he so desired. He rejected “Food Czar" Herbert Hoover’s suggestion that brewers be limited to using 50% of the grain they had used the year before. Wilson felt this was far too restriction noting,

"I take it for granted that such a reduction would by reducing the supply greatly increase the price of beer and so be very unfair to the classes who are using it, and who can use it with very little detriment when the percentage of alcohol is so small." (PWW 20 November 1917 45:91)

Wilson did not ban beer or wine, but restricted the alcohol content of the former to 3% by volume, and limited the alcohol content of beer to 2.75% by weight. Moreover, the amount of foodstuffs used to brew beer was limited to 70% of what had been used the previous year.(For more information on the Food Control Act please see the National Archives site on the Act's History.)

The 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act

The Anti-Saloon league, through its allies in Congress, introduced the Prohibition Amendment in 1917. It was submitted to the House of Representatives on April 4, 1917. The Senate received the resolution on July 30, 1917 and passed it August 1 by a vote of 65 to 20. The House got the bill again on December 17 and passed it with several changes. The House version gave Congress and the states the power to enforce the law, it set the date for enacting the law as one year after ratification, and it set a time limit of seven years for the amendment to be passed by the states (the Senate version had said six years). The Senate agreed to the House’s changes and the 18th Amendment was submitted to the states on December 22, 1917. The bill never came before Wilson as the President can neither sign or veto a constitutional amendment. It goes straight from the Congress to the states.

The amendment moved quickly through the states. With the ASL and the WCTU pushing state legislatures, the amendment was ratified by the thirty-sixth state on January 16, 1919 making the amendment part of the Constitution. By the end of February 1919, forty five of the forty-eight states had ratified the amendment. In the end, only Rhode Island and Connecticut never ratified it. Thus the 18th Amendment to the Constitution, the only one to date that restricted a freedom rather than defined or guaranteed one, was to become effective on January 16, 1920.

18th Amendment: Full Text

Section 1.

After one year from the ratification of this article the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited.

Section 2.

The Congress and the several States shall have concurrent power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Section 3.

This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by the legislatures of the several States, as provided in the Constitution, within seven years from the date of the submission hereof to the States by the Congress.

Ratified 16 January 1919.

Went into effect 16 January 1920

The Volstead Act

The 18th Amendment, however, did not include enforcement procedures, nor did it define what it meant by “intoxicating liquors.” Brewers and wine producers tried to convince Congress that the alcohol limit should be set high enough to allow light beers and wine while affecting only hard distilled liquors. This would match what the country was used to with the existing wartime restrictions. It also would have matched the US Army’s policies in Europe under General John Pershing’s General Order No. 77. Congress instead passed the far more restrictive Volstead Act, which set the legal alcohol limit to ½ of 1 % alcohol by volume.

Named after its sponsor, Andrew Volstead, Republican Representative from Minnesota, the act passed Congress easily. The House of Representatives passed it on 22 July 1919 by a vote of 287-100. The Senate passed it on 4 September without a roll call. The measure then had to go into conference. The conference bill passed the Senate on 8 October and by the House by a vote of 321-70 on 10 October. President Wilson vetoed the bill on October 27, but it was passed over his veto by the House by a vote of 176-55 on the same day. The Senate overrode the veto the next day, 28 October, by a vote of 65-20. The resulting law not only defined an intoxicating beverage as one containing more than one half of one percent alcohol by volume, it also gave federal agents the power to investigate and prosecute violations of the amendment. Individual states also had the right to enforce the law within their own boundaries.

The Volstead Act

Be it Enacted. . . . That the short title of this Act shall be the "National Prohibition Act."

The Volstead Act (1920)

Officially titled the National Prohibition Act

Effective Feb. 1, 1920

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Volstead Act, officially titled the "National Prohibition Act", was passed on Oct. 18, 1919 and went into effect Feb. 1, 1920. It effectively outlawed the production and sale of alcoholic beverages unless for religious or medical purposes. Allowed for possession or use of alcoholic beverages in private homes with legally acquired alcohol.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

TITLE I.

TO PROVIDE FOR THE ENFORCEMENT OF WAR PROHIBITION.

The term "War Prohibition Act" used in this Act shall mean the provisions of any Act or Acts prohibiting the sale and manufacture of intoxicating liquors until the conclusion of the present war and thereafter until the termination of demobilization, the date of which shall be determined and proclaimed by the President of the United States. The words "beer, wine, or other intoxicating malt or vinous liquors" in the War Prohibition Act shall be hereafter construed to mean any such beverages which contain one-half of 1 per centum or more of alcoholic beverages by volume.

SEC. 2. The Commissioner of, Internal Revenue, his assistants, agents, and inspectors, shall investigate and report violations of the War Prohibition Act to the United States attorney for the district in which committed, who shall be charged with the duty of prosecuting, subject to the direction of the Attorney General, the offenders as in the case of other offenses against laws of the United States; and such Commissioner of Internal Revenue, his assistants, agents, and inspectors may swear out warrants before United States commissioners or other officers or courts authorized to issue the same for the apprehension of such offenders, and may, subject to the control of the said United States attorney, conduct the prosecution at the committing trial for the purpose of having the offenders held for the action of a grand jury. . . .

TITLE II.

PROHIBITION OF INTOXICATING BEVERAGES.

SEC. 3. No person shall on or after the date when the eighteenth amendment to the Constitution of the United States goes into effect, manufacture, sell, barter, transport, import, export, deliver, furnish or possess any intoxicating liquor except as authorized in this Act, and all the provisions of this shall be liberally construed to the end that---the use of intoxicating liquor as a beverage may be prevented.

Liquor. . . . for nonbeverage purposes and wine for sacramental purposes may be manufactured, purchased. sold, bartered, transported, imported, exported, delivered furnished and possessed, but only as herein provided, and the commissioner may, upon application, issue permits therefore. . . . Provided, That nothing in this Act shall prohibit the purchase and sale of warehouse receipts covering distilled spirits on deposit in Government bonded warehouses, and no special tax liability shall attach to the business of purchasing and selling such warehouse receipts. . . .

SEC. 6. No one shall manufacture, sell, purchase, transport, or prescribe any liquor without first obtaining a permit from the commissioner so to do, except that a person may, without a permit, purchase and use liquor for medicinal purposes when prescribed by a physician as herein provided, and except that any person who in the opinion of the commissioner is conducting a bona fide hospital or sanatorium engaged in the treatment of persons suffering from alcoholism, may, under such rules, regulations, and conditions as the commissioner shall prescribe, purchase and use, in accordance with the methods in use in such institution, liquor, to be administered to the patients of such institution under the direction of a duly qualified physician employed by such institution.

All permits to manufacture, prescribe, sell, or transport liquor, may be issued for one year, and shall expire on the 31st day of December next succeeding the issuance thereof: . . . Permits to purchase liquor shall specify the quantity and kind to be purchased and the purpose for which it is to be used. No permit shall be issued to any person who within one year prior to the application therefore or issuance thereof shall have violated the terms of any permit issued under this Title or any law of the United States or of any State regulating traffic in liquor. No permit shall be issued to anyone to sell liquor at retail, unless the sale is to be made through a pharmacist designated in the permit and duly licensed under the laws of his State to compound and dispense medicine prescribed by a duly licensed physician. No one shall be given a permit to prescribe liquor unless he is a physician duly licensed to practice medicine and actively engaged in the practice of such profession. . . .

Nothing in this title shall be held to apply to the manufacture, sale, transportation, importation, possession, or distribution of wine for sacramental purposes, or like religious rites, except section 6 (save as the same requires a permit to purchase) and section 10 hereof, and the provisions of this Act prescribing penalties for the violation of either of said sections. No person to whom a permit may be issued to manufacture, transport, import, or sell wines for sacramental purposes or like religious rites shall sell, barter, exchange, or furnish any such to any person not a rabbi, minister of the gospel, priest, or an officer duly authorized for the purpose by any church or congregation, nor to any such except upon an application duly subscribed by him, which application, authenticated as regulations may prescribe, shall be filed and preserved by the seller. The head of any conference or diocese or other ecclesiastical jurisdiction may designate any rabbi, minister, or priest to supervise the manufacture of wine to be used for the purposes and rites in this section mentioned, and the person so designated may, in the discretion of the commissioner, be granted a permit to supervise such manufacture.

SEC. 7. No one but a physician holding a permit to prescribe liquor shall issue any prescription for liquor. And no physician shall prescribe liquor unless after careful physical examination of the person for whose use such prescription is sought, or if such examination is found impracticable, then upon the best information obtainable, he in good faith believes that the use of such liquor as a medicine by such person is necessary and will afford relief to him from some known ailment. Not more than a pint of spirituous liquor to be taken internally shall be prescribed for use by the same person within any period of ten days and no prescription shall be filled more than once. Any pharmacist filling a prescription shall at the time indorse upon it over his own signature the word "canceled," together with the date when the liquor was delivered, and then make the same a part of the record that he is required to keep as herein provide . . . .

SEC. 18. It shall be unlawful to advertise, manufacture, sell, or possess for sale any utensil, contrivance, machine, preparation, compound, tablet, substance, formula direction, recipe advertised, designed, or intended for use in the unlawful manufacture of intoxicating liquor. . . .

SEC. 21. Any room, house, building, boat, vehicle, structure, or place where intoxicating liquor is manufactured, sold, kept, or bartered in violation of this title, and all intoxicating liquor and property kept and used in maintaining the same, is hereby declared to be a common nuisance, and any person who maintains such a common nuisance shall be guilty of a misdemeanor and upon conviction thereof shall be fined not more than $1,000 or be imprisoned for not more than one year, or both. . . .

SEC. 25. It shall be unlawful to have or possess any liquor or property designed for the manufacture of liquor intended for use in violating this title or which has been so used, and no property rights shall exist in any such liquor or property. . . . No search warrant shall issue to search any private dwelling occupied as such unless it is being used for the unlawful sale of intoxicating liquor, or unless it is in part used for some business purposes such as a store, shop, saloon, restaurant, hotel, or boarding house. . .

SEC. 29. Any person who manufactures or sells liquor in-violation of this title shall for a first offense be fined not more than $1,000, or imprisoned not exceeding six months, and for a second or subsequent offense shall be fined not less than $200 nor more than $2,000 and be imprisoned not less than one month nor more than five years.

Any person violating the provisions of any permit, or who makes any false record, report, or affidavit required by this title, or violates any of the provisions of this title, for which offense a special penalty is not prescribed, shall be fined for a first offense not more than $500; for a second offense not less than $100 nor more than $1,000, or be imprisoned not more than ninety days; for any subsequent offense he shall be fined not less than $500 and be imprisoned not less than three months nor more than two years. . . .

SEC. 33. After February 1, 1920, the possession of liquors by any person not legally permitted under this title to possess liquor shall be prima facie evidence that such liquor is kept for the purpose of being sold, bartered, exchanged, given away, furnished, or otherwise disposed of in violation of the Provisions of this title. . . . But it shall not be unlawful to possess liquors in one's private dwelling while the same is occupied and used by him as his dwelling only and such liquor need not be reported, provided such liquors are for use only for the personal consumption of the owner thereof and his family residing in such dwelling and of his bona fide guests when entertained by him therein; and the burden, of proof shall be upon the possessor in any action concerning the same to prove that such liquor was law fully acquired, possessed, and used. . . .

Enforcement

The resulting law was far stricter than many people expected. This added to problems with enforcement. Some states took the law more seriously than others. Maryland, for example, remained thoroughly “wet” and refused to make more than a token effort at enforcement. Neighboring Virginia, however, attempted to enforce the law. In general, Prohibition was considered to be a failure. Drinking alcoholic beverages never stopped during the 13 year experiment, but when Prohibition was repealed in 1933, the amount of alcohol people consumed was less than it had been when Prohibition had been enacted.

A raid on a Washington, D.C. speakeasy, circa 1923.

Photo from the author's collection.Further Reading

For more on Prohibition please see my page on the history of prohibition in Virginia and on The Wickersham Commission (1929-1931) which tried to find a way to make Prohibition work.

Selected Sources Used

Deliver Us from Evil: An Interpretation of American Prohibition. By Norman H. Clark, W.W. Norton. 1985. As much sociology as history this book is one of the best short works on Prohibition.

Domesticating Drink: Women, Men, and Alcohol in America, 1870-1940. (Gender Relations in the American Experience). by Catherine Gilbert Murdock, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999. A useful social history about changing gender roles.

Organized for Prohibition: A New History of the Anti-Saloon League. by K. Austin Kerr, Yale, 1985. How Wilson lost “dry” support as President.

Prohibition and the Progressive Movement. by James H. Timberlake, Harvard, 1963. Explains Wilson's opposition to Prohibition. Attributes Prohibition support to the old-stock, Protestant middle class as part of Progressivism.

Prohibition: The Lie of the Land. by Sean Dennis Cashman, Free Press, 1981. Argues Wilson’s background may have led him to support Prohibition, but his political instincts caused him to oppose it.

Repealing National Prohibition. by David E. Kyvig, University of Chicago Press, 1979.

Retreat from Reform: The Prohibition Movement in the United States, 1890-1913. by Jack S. Blocker, Greenwood, 1976.

Shaping the Eighteenth Amendment: Temperance Reform, Legal Culture, and the Polity, 1880-1920. (Studies in Legal History). by Richard F. Hamm, University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Thanks to Joseph E. for the correction!updated 9 December 2008