Introduction:The following is a very rough draft of an article on Prohibition in the state of Virginia. A radically rewritten, peer-reviewed and edited version of this article was accepted by the British Journal Brewery History and appeared in their Winter 2010-2011 issue. |

Virginia and Prohibition

Virginia went dry in November 1916, three years before national prohibition began. Although Virginia established statewide prohibition through a popular referendum, it nonetheless faced several challenges in enforcing the new law. Its long coastline made it difficult to prevent smuggling, i.e. rum-running. It bordered on a wet state, Maryland, which made barely an effort to enforce national dry laws from 1920-1933. Virginia contained several cities which were reluctantly dry, most notably Alexandria, Richmond and Norfolk. In addition, Virginia had a long-established moonshining tradition in the mountainous western part of the state. As a result, Virginia struggled to live up to the dry ideal it set for itself in 1916.

Virginia’s experiment with prohibition did not come about suddenly. As was often the case throughout the country, Virginia went dry only after a long, protected political battle led by groups such as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and the Anti-Saloon League (ASL). It was these interest groups that provided the leadership, the voters, and the impetus behind the dry campaign that lead to Virginia's attempt to ban alcoholic beverages.

The WCTU and the Anti-Saloon League in Virginia

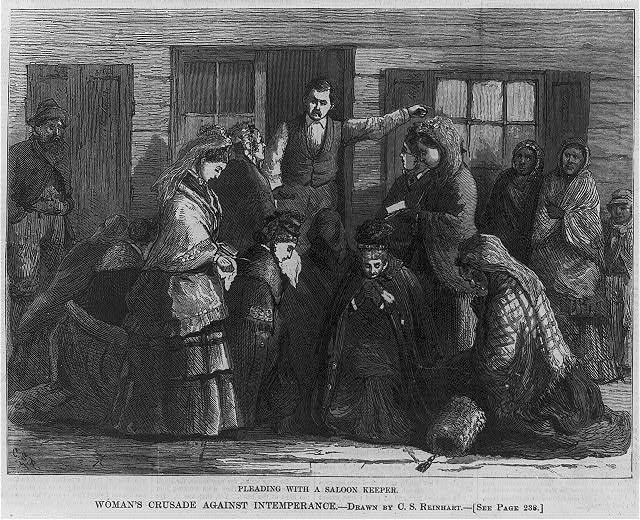

The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union was founded in 1874 as a result of a woman’s temperance crusade in the north. A popular prohibition speaker--Dr. Dio Lewis--was traveling through New York and Ohio in December 1873 talking to church groups and telling them how his mother and some of her friends closed saloons in 1830 through prayer. He inspired the women in a Fredonia, New York audience to use the same tactic in their home town. However, it was in Hillsboro, Ohio, that the movement really got started. After Lewis’s prohibition lecture at Hillsboro Presbyterian Church, seventy of the women in the audience marched out singing hymns and began to pray in and in front of the town's saloons until the owners agreed to close. The movement spread to other towns in Ohio and New York and in 1874 the groups organized themselves as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union in Chautauqua, New York.

"Pleading with a saloon-keeper." Harper's Weekly, v. 18, (1874 March 14), p. 237. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540

The Virginia WCTU was founded in September 1882 at the Y.M.C.A. in Richmond Virginia. The Richmond chapter soon began spreading into other Virginia towns; Alexandria, Charlottesville, and Staunton that first year, Harrisonburg and Dayton in 1883, as well as another chapter in Richmond. Also in 1883 the first state Convention for the Virginia WCTU was held at the Seventh Street Christian Church in Richmond. The Virginia chapter, like the national organization, concentrated on educational campaigns, printing literature and lobbying for anti-alcohol education programs in schools. Under the leadership of national WCTU President Francis Willard (1839-1898), however, the Virginia WCTU supported the Prohibition Party, rather than dry Republicans or Democrats. This only limited the WCTU’s influence in the state. While the WCTU remained active and influential, especially in mobilizing women activists, their place as the leading prohibition organization after 1900 was taken by the Anti-Saloon League which was much more pragmatic about which candidates to support.

The national Anti-Saloon League (ASL) was founded in Ohio in 1893 and had its national offices in central Ohio with a legislative branch office in Washington, D.C.. They began establishing contact with various Virginian anti-liquor activists in the 1890s, but initial attempts to found ASL chapters in Virginia failed. The ASL’s initial difficulties in organizing chapters in Virginia were matched by its trouble organizing in the rest of the South. The South already had churches active in dry campaigns, which seemed to provide a fertile ground for recruitment. However, many Southerners remained suspicious of northern organizations. Moreover, the ASL did not agree with Southern racial segregation, although they were sometimes willing to use it to their advantage. For example, in 1908 the Tennessee ASL reported that the labels on gin bottles sold by a St. Louis company to southern blacks featured labels with half-dressed white women in “suggestive” poses. The Tennessee ASL charged that the gin dealers were abetting assaults by African American men on white women. At other times the ASL seemed tone-deaf to politics in the South. The ASL’s newspaper, ”American Issue” was published in each state, but only two to four pages of each issue would be local material. The remaining ten to twelve pages came from the Ohio office. In 1908 “American Issue” ran a story on an Ohio temperance speech in which southern secession was compared to a “slimy serpent hissing disunion." Such anti-southern images did nothing to help the ASL organize in the region.

The ASL’s main problem in organizing the region, however, as noted by historian William Link, is that Southern progressives (including the prohibitionists) had to combat a regional predilection for political decentralization. The ASL was organized like a corporation with a central office in Ohio, but such centralized control conflicted with Southern political traditions of local control. In order to be effective in the South the ASL would have to convince Southern voters that state control of liquor would be worth the cost of giving up some elements of local rule.

Along with entrenched localism, the Anti-Saloon League also had to deal with the question of African American voters. The ASL would not be able to focus attention on wet vs. dry issues until southern fears were eased that African Americans might win political power if the white electorate were divided between wets and drys. Moreover, established political interests could always derail reform campaigns by claiming that they wanted to politically empower non-whites.

The Readjusters

As with many other states in the decades after the Civil War, Virginia was essentially a one party state with competing factions. Virginia was under the firm control of the Democratic Party which was run by a dominant political organization. The Virginia political machine was opposed by a Democratic reform faction, a small Republican Party, and a substantial reform faction of independents nicknamed the "readjusters." Between 1879-1882 the readjusters under the leadership of General William Mahone (CSA) controlled every part of the state government and pushed through series of reforms including increased spending on public schools, tax relief for poor farmers, and turning over part of the anti bellum state debt to West Virginia. Mahone was elected U.S. Senator in 1880 but when he started to ally with the Republican Party he lost support and the readjusters were ousted from power.

General William Mahone.

General William Mahone.

The readjusters, however, both frightened and motivated the Democratic Party machine in Virginia. African-Americans had begun voting again under Mahone’s influence and one of the machine's main concerns was isolating any non-whites from political power. To the Democratic political machine, prohibition voters appeared as a threat because they might drain votes away from white machine candidates allowing Republicans and their readjuster allies to win office.

The Virginia Constitutional Convention 1901-1902

In 1891 in Richmond a state-wide temperance convention met at the request of the Baptist General Association in order to find some basis for unified action against liquor. The movement for this convention was led by John R. Moffett, pastor at a small Baptist church in Danville. He had campaigned against liquor in Norfolk, in Roanoke, and throughout the state through the newspaper "Anti-Liquor." In late 1892 he was murdered by a former bar tender, a man "of low character." The 1891 Convention, however, set in motion a momentum for prohibition that far out-lived Moffett.

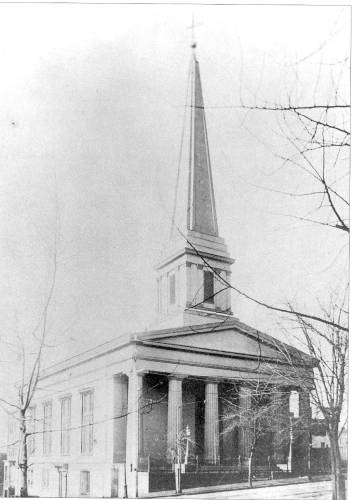

In 1901 a small convention assembled in the basement of Richmond’s Second Baptist Church and formed the Virginia Anti-Saloon League. Dr. S.C. Mitchell was named President and Rev. C. H. Crawford was named superintendent. Crawford began using an ASL newspaper, the “Christian Federation.” He also became somewhat of a celebrity for the ASL in 1902 when he was attacked by a judge using a whip. In Amherst Virginia a druggist went to trial for selling 30 barrels of “medicinal whiskey” in only a year. Judge C.F. Campbell instructed the jury in the druggist’s trial in such a way that they had to find him innocent. Crawford wrote in the “Christian Federation” that it wasn't clear which was doctored more, the whiskey or the judge. In response Campbell tried to convict Crawford of contempt. When that failed he publicly whipped Crawford. Judge Campbell was impeached for his action and removed from the bench. Crawford used the attack as an example of the wets’ corruption to good effect. By January 1903 sixty out of 135 Virginia counties had organized ASL chapters.

Richmond's Second Baptist Church. Circa 1900. Used with permission.

Richmond's Second Baptist Church. Circa 1900. Used with permission.

At the same time the Virginia ASL was being organized, political attention was focused on a constitutional convention which was writing a new state constitution. The main order of business was how to disenfranchise African-Americans in the state without technically violating the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. While trying to assure poor white voters that “no white man would lose his vote,” the delegates decided that under the state’s new constitution, a man would be eligible to vote if he could satisfy one of three requirements:

- he could read or understand the state constitution

- he had paid taxes on property worth at least $333

- he was either a U.S. or Confederate veteran or the son of a veteran.

The franchise was restricted further by setting age, residency, and literacy restrictions as well as a poll tax. Legally, according to the General Assembly, the new constitution had to be ratified by the voters of Virginia. Fearing the reaction by voters who were about to be disfranchised, the Convention instead proclaimed the Constitution of 1902 to be law and in effect as of July 1902. As a result, the old voting rolls were purged and the Virginia electorate was cut in half.

The ASL tried to amend the new constitution while it was being written by proposing a provision that no license to make or sell any alcohol be granted, unless requested in writing by a majority of voters within a given precinct. The resolution was met with opposition not just by wet forces, who threatened to fight against the new constitution if it were included, but also by some dry supporters who felt that it was too radical and would thus provoke public opinion against all local option campaigns. The opposition within the dry ranks proved to be decisive and the resolution failed. Another ASL measure calling for a referendum to be held in 1905 on state-wide prohibition also failed because some dry leaders believed that the public was not yet supportive enough of dry legislation to risk a general election.

The failure of the ASL to have its radical provisions included in the new constitution forced it to move to more gradual methods. Passing local option and other piecemeal laws were part of the ASL’s strategy to convince the public to support full “bone dry” prohibition laws. In 1903 the Mann Law, named for Senator William Hodges Mann of Nottoway, made most of rural Virginia dry by setting very complex procedures to purchase a liquor-selling license. For example, in a district or town with less than 500 people a judge granting the license had to decide not only that the person requesting the license was of good character, but that a majority of people in that district favored the license. This provision automatically counted those who did not care if a license was granted in the “dry” column.

This law was strengthened in 1908 with another “Mann Law” sometimes also called the “Byrd Law” after Speaker of the Virginia House, Richard E. Byrd (father of Admiral Richard Byrd and Senator Harry Byrd). The 1908 law defined liquor as “all mixtures, preparations and liquids which will produce intoxication” and outlawed any malt drink with an alcohol content greater than 2.25 percent. It also eliminated the possibility that a judge might issue a permit to sell alcohol in any district of under 500 people simply by not including any procedures for such a permit to be issued. It outlawed so-called “private clubs” which sold alcohol in dry areas. It prohibited selling liquor from a still in dry areas, thus closing a loophole that allowed some stills to operate. It also increased regulations regarding selling liquor on passenger trains, at drug stores, or giving out “samples.” It also increased regulations on making cider (even non-intoxicating), wine, and malt drinks (such as beer). Finally, it increased the allowable measures police could take in enforcing dry laws. The result of the Byrd Law was not a dry Virginia, but one in which most alcoholic beverages were limited to a few large towns and cities. Virginia had moved to the very edge of being completely dry.

Virginia Goes Dry

In 1904 the Virginia Anti-Saloon League gained a new President, who would not only be instrumental in making Virginia dry, but also the entire U.S.. The Reverend James Cannon Jr. was principal of Blackstone Female Institute and a Methodist minister. A delegate to the Virginia Methodist Conference, he was also the editor of the Conference newspaper, the Baltimore and Richmond Christian Advocate, and wrote on moral and social issues in the church, particularly prohibition. Cannon’s energy and political skills, plus a long-held devotion to the anti-alcohol cause, would propel not only Virginia into the dry column, but would make Cannon one of the most important prohibitionist leaders in the country.

Cannon was active in the campaign to pass the 1908 Mann Law and after it was passed began to look towards at last passing state-wide prohibition. Other southern states in 1907-1908 besides Virginia were considering the alcohol issue. Alabama and Georgia in 1907 had state-wide prohibition measures pass via their legislatures. In 1908 Mississippi joined the dry ranks. Even states that did not go entirely dry in this period, such as Arkansas, passed local option laws. It seemed to Cannon as if the political momentum was fast shifting to the drys throughout the region.

With the passage of the Byrd Law the ASL under Cannon had clearly demonstrated its political clout in the state. With a gubernatorial election coming in 1909, and with an eye to the voting bloc represented by the ASL, the conservative Democratic political machine headed by U.S. Senator Thomas S. Martin considered who to back for governor. Despite the Martin machine being normally wet, they chose a well known dry, State Senator William Mann, the Vice-President of the Virginia ASL. The independent reform Democrats chose Henry St. George Tucker, a vocal, if moderate, wet. The conservative’s choice of Mann proved to be a wise one, as Cannon decided to ally the ASL with the Martin political organization against the reformers.

Governor William Hodges Mann (1843-1927)

Governor William Hodges Mann (1843-1927)

The wet press accused Cannon of making an immoral deal with Martin, using the machine’s support in exchange for a promise that no new prohibition legislation be introduced while Mann was governor. In his book, “Dry Messiah” author Virginus Dabney quotes the former Senate Clerk as claming that he was present when Martin and Cannon made this deal: Martin would support Mann in exchange for Cannon’s promise not to introduce new prohibition legislation in the Virginia while Mann was governor. There is no definitive proof, however, that such a deal existed. Cannon, not unexpectedly, denied such as deal, as did the other parties affected. Cannon and Martin were also both skilled politicians and would have appreciated the advantage such an alliance would bring, even without an explicitly-stated bargain. Martin knew with the ASL’s dry votes, any candidate he supported would win, and Cannon knew that further extension of prohibition in Virginia lacked popular support. Mann came out publicly in favor of local option in opposition to full state-wide prohibition in early 1909, assuring the conservative wets knew that full prohibition would be at the least delayed. At the same time Cannon knew that with Mann in the governor’s chair, then the ASL would be in a dominate position in the state government.

Despite the rumored deal, anti-prohibition legislation did come before the Virginia legislature during Mann’s tenure as governor. During the 1910 legislative session, a bill calling for a statewide referendum on prohibition were submitted but failed. Governor Mann refused to support the bill, noting that he had been elected on a local option platform. During the 1912 session another prohibition referendum bill was submitted. More dry members had been elected to the lower house during the 1911 mid-term elections, but the state senate remained under the control of the wet political machine controlled by Senator Martin. Cannon pressed for the referendum bill’s passage during the 1912 session. He met with legislators, testified in favor of the bill in committee hearings, and was a prominent figure in the Senate public gallery where he conspicuously took notes during debates. He even threatened to split with Martin, growling that “the parting of the ways has been reached.” Despite Cannon's efforts, the referendum bill failed again, passing the House easily, but losing in the Senate by a vote of 16 in favor and 24 opposed.

In his memoirs Cannon quoted an editorial he published after the Senate vote asking, “do the leaders of that party [Martin’s Democrats] propose to allow the ‘wet’ cities of Virginia to defeat all moral legislation?” He leveled a clear challenge to Martin not to take the dry Democrats’ support for granted…

Moral issues are supreme, and party policy must conform to aroused moral sentiment, or the framers of the party policy will go down in defeat, and the new man will be selected who will conform the party policy to moral sentiment.

Having fired his shot across Martin’s bow, Cannon and the ASL began their preparations for the 1914 legislative session.

While efforts to pass the referendum bill in 1910 and 1912 failed, during Mann’s four years as governor (1910-1914) Cannon and the ASL did more than simply lobby in Richmond. Knowing that increased public support was necessary to win a referendum on prohibition the Cannon created an extensive propaganda apparatus for the ASL in Virginia. All of the major newspapers in the state were wet, so in January 1910, just as Mann took office, Cannon started his own newspaper, the Richmond Virginian. Published six days a week, the Virginian advertised itself as “A Clean Paper for the Home.” Until Cannon sold it in 1920, the Virginian proved to be a continual drain on its owner’s finances. It survived on subscriptions, loans and gifts from wealthy supporters. However, Cannon used it to attack the wets, especially the other Richmond newspapers, to pressure elected officials, and to preach the gospel of prohibition throughout the state.

The 1914 Referendum

When the 1914 legislative session began, Cannon and the ASL believed that the time was right to push a referendum bill through both houses. In the 1913 elections Henry C. Stuart had been elected governor and he promised that he would sign any referendum bill. The newly elected Lieutenant Governor was J. Taylor Ellyson and he promised that in case of a tie vote in the Senate he would vote for the referendum bill. The only remaining obstacle was a handful of Senators who answered to Martin. They had been successful in killing the bills in 1910 and 1912. However, in 1914 Cannon had a new weapon to use against Martin. Also elected in 1913 had been a new Attorney General, John G. Pollard; a reformer who had formed a new organization to fight Martin’s organization. Pollard’s organization, the Virginia Progressive Democratic League, was not powerful enough to defeat Martin’s machine, unless they aligned with Cannon’s supporters. Martin’s ally, Richard E. Byrd noted that “this could produce some ugly complications. I cannot help thinking that the defeat of the [referendum bill] would prove disastrous in many ways.”

|

The Virginia Anti-Saloon League meeting in Richmond, 1914. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In January 1914 a bill titled the “Williams Enabling Act”passed the House by a vote of 75-19. It provided for a referendum on state-wide prohibition . The Senate vote was expected to be close and if Martin again instructed his men to vote against it, there would be enough votes to prevent it from passing. Unlike in 1910 and 1912 however, there was a perspective third party--the Virginia Progressive Democratic League--who might gain Cannon’s support against Martin's political machine in the next election. Faced with the possibility of Cannon siding with reformers against the Senator's organization, Martin decided to make the best of the situation, and give Cannon and the ASL what they wanted. Martin instructed the swing vote Senators to vote in favor of the bill.

Despite Martin’s capitulation, however, the vote was still close. Facing defeat, the night before the vote a group of wets took a senator who voted dry but was personally wet, out for an evening’s entertainment at a "house of ill repute." Early the next morning several of Cannon’s men found the Senator, the worse for wear after a night of heavy drinking and carousing, and helped him stumble back to the Senate chambers to cast the final vote. The drunken Senator’s vote created a 20-20 tie, but Lieutenant Governor Ellyson cast his promised vote in favor and the bill passed.

The referendum was scheduled for September 22, 1914. Despite wet protests, the ballot would present the voter with two simple choices, “For State-Wide Prohibition” and “Against State-Wide Prohibition.” The referendum opponents had wanted the opposing choice to read “For Local Option” which would allow moderate drys to vote against the state-wide option while still technically voting dry. By starkly wording the ballot as a straight up or down vote on prohibition the drys hoped they would capture more of the moderate drys' votes.

During the seven months between the enabling bill’s passage and the referendum Virginia’s voters were inundated with campaign propaganda from both wets and drys. Most of the state’s major newspapers were wet, with the obvious exception of Cannon’s Virginian. Cannon spoke at rallies and meetings throughout the state and published a stream of editorials, in one typical example proclaiming that alcohol produced only “pauperism and insanity and crime and shame and misery and broken hearts and ruined homes and shortened, wasted lives.” The dry campaign put on parades and rallies. Speakers and printed material alike emphasized the cost to home life from liquor, using women and children to emphasize their “protect the home” theme. Get rid of the liquor trade, they promised, and the levels of crime, poverty, broken homes and mental illness would all drastically decrease.

Pro-Prohibition rally newspaper advertisement, September 21, 1914.

The wets were not as organized as the drys, but they still were represented by groups such as the Association for Local Self-Government (ALSG). The ALSG was based in the Richmond Chamber of Commerce building and included numerous influential businessmen from around the state as well as judges and lawyers from the state bar association. The ALSG started its campaign with a rally at the Academy of Music on May 14. ALSG leaders spoke to a crowd of 2,000 claming that prohibition “violates the fundamental principle of local self-government, and has invariably caused social and political unrest, bitterness and hypocrisy, and has brought the law into contempt.” They also published a newspaper titled the Trumpeter which ran anti-prohibition editorials and news articles. They also printed broadsides, pamphlets, booklets, anything to carry the message that prohibition would only create more problems that it would solve.

The ALSG had to expand outside of the state capital, however, but most of their leaders were from Richmond and limited in their statewide contacts. They picked Henry St. George Tucker, who had lost the 1909 Governor’s election to Judge Mann, as their leader. Tucker was associated with the non-machine faction of the Democratic Party which would be useful since the Martin machine had ties to the liquor interests. Tucker wrote out a statement on local option to be distributed throughout the state. He refused to go on a statewide speaking tour, but helped the ALSG put together a list of prominent local Democrats who would speak within their own Congressional districts against state-wide prohibition. The result was a state-wide “Executive Committee.”

The wet campaign followed a pattern familiar from other state prohibition campaigns. Prohibition, they argued, was not only a violation of local self-rule, it would deprive the state of over $600,000 a year in tax revenue, which would require an increase in other taxes to make up the difference. Drunkenness and other abuses would only be driven underground, and the drys’ claims that crime and poverty would drop were false. Moreover, according to the wet campaign, prohibition would increase popular disrespect for the law because average citizens would not respect the dry law and would ignore it. In short, the wets argued, because prohibition would be an unpopular law, it would be unworkable.

The wets were handicapped by not being able to openly argue that drinking was a good thing in itself. Dry educational campaigns had been pressing the idea that alcohol was a poison far too long and far too successfully to argue against prohibition on any grounds except personal liberty. This also meant that those businesses that were most obviously affected by prohibition--breweries, wineries, distillers, and their dealers and saloons--had to keep a low profile and find a way to launder their campaign donations through front groups. Any group opposed to prohibition that openly took money from the alcohol industry faced being charged with being allied with, in Cannon’s words, “the most unscrupulous organization of capital in the world.” In an attempt to overcome this handicap the wets outspent the drys by a factor of at least four to one.

Both sides predicted victory before the election. The wet press expressed confidence that the “zealots” would be rebuffed by the voters. A headline in the Alexandria Gazette the day before the election forecast “Prohibition will be defeated by no less than 10,000 majority.” The Richmond Times-Dispatch, one of Bishop Cannon’s main antagonists, was more cautious noting that both sides were predicting a large victory. The Times-Dispatch editorial page, however, clearly took sides, noting on the morning of election day,

Left to themselves the vast majority of the people of the State, upon whom Virginia’s prosperity and progress depend, would not have dreamed of attacking local self-government in order to agitate state-wide prohibition, a system which makes the liquor traffic immensely more complex and menacing than it can be and is under local option. The agitation has come from without.

The drys' long propaganda campaign paid off on Election Day. The referendum passed by a vote of 94,251 in favor and 63,886 opposed. Of Virginia’s 100 counties, 71 voted in favor of prohibition. Eight of the ten congressional districts went dry, and one of the remaining two was wet by only ten votes. Surprisingly, sixteen of the state’s twenty cities also voted in favor of going dry. Traditionally cities were strongholds of wet votes. However, only Arlington, Norfolk, Williamsburg and Richmond stayed wet. Accordingly, following the referendum, the Virginia legislature quickly passed a prohibition law, called the Mapp Law after state Senator Walter Mapp of Accomack County, making the entire state dry as of midnight, the morning of November 1, 1916.

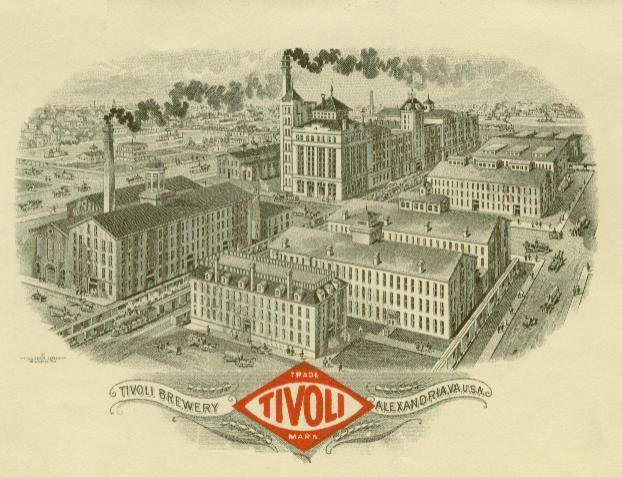

Robert Portner's Brewing, Alexandria.

The new dry law closed numerous distillers, six breweries, as well as several hundred saloons, in addition to taking away business from bottling companies and distributors. Breweries and distillers were allowed to stay in business so long as they sold their product out of state. Five of the six Virginia breweries stayed open until 1918. Only Robert Portner’s in Alexandria closed immediately. Because the Mapp Law prohibited the production all malt beverages for instate use, even near beer, several breweries turned to making soda pop and bottled water instead. For example, Richmond's Home Brewing Company became the Home Products Company and made soft drinks. The Virginia Brewing Company in Roanoke attempted to survive prohibition the same way.

A Dry Virginia

Virginia’s prohibition law was in some ways stricter than those passed in other states. As noted above, breweries in Virginia were prohibited from producing any malt products for sale in-state. Breweries in other states with less restrictive laws survived nationwide prohibition by making malt syrup for “home baking”, in reality servicing home brewers, or by making near beer which could be spiked with alcohol. The Mapp law defined “ardent spirits” as “alcohol, brandy, whiskey, rum, gin, wine, porter, ale, beer, all malt liquors, absinthe, and all compounds or mixtures of any of them.” The phrase “all malt liquors” was worded to include both intoxicating and non-intoxicating drinks made of malt.

Virginia’s law did have some loopholes however, so it wasn't quite the bone dry regime that the ASL had originally hoped to establish. As noted above, manufactures of alcoholic beverages were allowed to continue production, if the product were meant for sale in another state where such products were legal. Moreover, some home consumption was allowed if the user had purchased the alcohol before November 1, 1916.

Despite the ASL's high hopes, Virginia also had the same difficulties enforcing prohibition that the rest of the country faced. Most of the neighboring states were dry. North Carolina had established state-wide prohibition in 1908, West Virginia in 1914 and Tennessee followed in 1917. Washington, D.C. went dry in November 1917 which closed a small opening for alcohol smuggling. However, there remained four major outlets for rum running that were never successfully closed. To the north Maryland remained resolutely wet, with the exception of a few legally dry counties. Annapolis only made a bare effort at enforcement even during nationwide prohibition from 1920-1933. Maryland Governor Albert Ritchie went so far as to declare that prohibition was a federal law, so the federal government could enforce it!

Virginia shares the Chesapeake Bay with Maryland, and the bay seemed as if it were designed for smuggling with its many small islands, coves and inlets. Norfolk had been wet during the referendum and remained a popular spot for smugglers to import alcohol. Finally, Virginia had a long-standing tradition of moonshining, especially in the western mountains, an area which traditionally resented Richmond’s control. Moonshiners found that prohibition furnished an even larger market for their product.

A short silent film about a raid circa 1932 on a still in rural Virginia. Film in author's collection. Apx 1 MB.

A short silent film about a raid circa 1932 on a still in rural Virginia. Film in author's collection. Apx 1 MB.

Repeal

By 1933 Virginia seemed ready to join the movement to repeal Prohibition. The benefits promised by the ASL and the other drys--such as an end to most crime and poverty--had never materialized. Indeed, the national depression and the growth of organized criminal gangs seemed to make a mockery of such promises. In the 1932 presidential election Virginia went for Franklin Roosevelt, who promised among other things to end prohibition, over the dry Herbert Hoover winning 68% of the vote. In March 1933 the U.S. Congress passed the Cullen-Harrison Act which legalized the sale of beverages containing not more than 3.2 percent alcohol by weight. However, Virginia still had a state-wide prohibition law in effect and Virginia Governor John G. Pollard was a dry. However, Senator Harry Byrd convinced Pollard that there was strong enough support for repeal to call the Virginia General Assembly into special session. The Assembly met in Richmond on August 17, 1933.

The General Assembly did three things at the special session:

1. Legalized the sale of 3.2 percent alcoholic beverages.

2. Called for a special election to decide whether to continue State Prohibition if National Prohibition was repealed or, in place of State Prohibition, to adopt a "plan of liquor control".

3. Created a committee to draft legislation in the event Virginians voted to end prohibition in Virginia.

The special election was held on October 3, 1933. The vote to end state prohibition was 99,640 to 58,518 in favor and the vote to devise a plan of liquor control to take the place of State Prohibition passed 100,445 to 57,873. Delegates elected by the voters formally ratified the 21st amendment at a special convention held October 25, 1933. Virginia was the 32nd state to ratify the 21st amendment.

The Assembly committee responsible for recommending the best plan of liquor control studied the control systems used by other states. The committee recommended a combination monopoly and license system patterned after the system then used in Quebec, Canada. The plan called for all hard liquors to be sold by the state with lighter beverages to be dispensed by licensees of the state. The committee also recommended that the system be administered by a three-man Alcoholic Beverage Control Board with certain powers to enforce liquor control in the State. The committee's final report, along with proposed legislation designed to implement its recommendations, was well received by the 1934 General Assembly. The plan was adopted virtually intact on March 7, 1934, and the first three Board members of the Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control were appointed: Mr. T. Mc Call Frazier, Major S. Heth Tyler, and Colonel R. McCarthy Bullington. Virginia's dry spell had lasted 18 years.

Virginia Prohibition Timeline

1901 The Virginia Anti-Saloon League is founded at a meeting in Richmond.

1903 Virginia passes the Mann Law, practically banishing all saloons from rural districts. The law set up such stringent requirements for allowing alcohol sales in small towns and rural areas that it effectively made them dry. This closed about ¼ of saloons in Virginia. Also, twenty-four towns and cities have elections on local option, eighteen of them go dry.

1906 Six more towns vote to go dry.

1907 Thirteen towns have vote son local option, eleven go dry. The Twelfth National Convention of the Anti-Saloon League is held in Norfolk.

1909 The Anti-Saloon League estimates that only about 600 saloons remain in Virginia. Charlottesville votes to go dry.

1910 Attempts to reverse prohibition in Winchester and Fredericksburg fail as both vote to remain dry.

1911 The Anti-Saloon league reports that eight of the 19 cities in Virginia are dry, as are 145 of 161 towns. The rural areas of the state are almost entirely dry as well.

1912 The House of Delegates in Virginia’s legislature passes a resolution to put statewide prohibition on a referendum in the Fall, but the bill is defeated in the Senate by a vote of 24-16.

1914 The bill for an election on statewide prohibition passes both houses of the legislature, the lower house by a large margin, and the Senate when the Senate President cast a tie-breaking vote. The election as held September 22. Statewide Prohibition passes 90,000 to 60,000 (approximate totals). Statewide prohibition begins at Midnight, the morning of November 1, 1916.

1916 October 31/November 1. Statewide prohibition begins at midnight.

1918 January 11. Virginia is the second state to ratify the 18th Amendment.

1933 August 17. The Virginia legislature meets in special session legalizing 3.2% beer and making arrangements for a referendum on Prohibition. October 3. In a special election, voters vote to end statewide prohibition. October 25. A state convention ratifies the 21st amendment. Virginia is the 32d state to ratify.

1934 March 7. Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control is established.

Breweries Closed by Virginia’s Dry Law

Alexandria

Robert Portner, aka Tivoli Brewery. (closed 1916)

Norfolk

Consumer’s Brewing Company (closed 1918, reopened 1934)

Richmond

Richmond Brewery (closed 1918)

Home Brewing (closed 1918, reopened 1934)

Roanoke

Virginia Brewing Company (closed 1918, reopened 1934)

Rosslyn

Arlington Brewing Company (closed 1918)

Sources

Links

Virginia Constitutional Convention

Second Baptist Church, Richmond.

Bibliography

Benson, T. B. A Treatise on the Virginia Prohibition Act. (Charlottesville: L. F. Smith and W.F. Souder, Jr. 1916).

Cannon, James Jr. Bishop Cannon’s Own Story: Life as I Have Seen it. Richard L. Watson Jr., editor. (Durham: Duke University Press, 1955).

Cherrington, Ernest H. The Evolution of Prohibition in the United States of America. (Westerville, Ohio: American Issue Press, 1920).

Dabney, Virginus . Dry Messiah: The Life of Bishop Cannon. (New York, 1949).

Hamm, Richard F. “The Killing of John R. Moffett and the Trial of J .T. Clark: Race, Prohibition, and Politics in Danville, 1887-1893” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 101:3 (1993) 375-404.

Hohner, Robert A. “Bishop Cannon’s Apprenticeship in Temperance Politics, 1901-1918 ” The Journal of Southern History. 34:1 (February 1968) 33-49.

Hohner, Robert A. “Prohibition and Virginia Politics: William Hodges Mann versus Henry St. George Tucker, 1909” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 74 (1966) 88-107.

Hohner, Robert A. “Prohibition Comes to Virginia: The Referendum of 1914” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 75 (1967) 473-488.

Hohner, Robert A. Prohibition and Politics: The Life of Bishop James Cannon Jr. (Columbia: University North Carolina Press, 1999).

Ironmonger, Elizabeth Hogg and Pauline Landrum Phillips. History of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union of Virginia and a Glimpse of Seventy-Five Years, 1883-1958. (Richmond: Cavalier Press, 1958).

Kerr, K. Austin. “Organizing for Reform: The Anti-Saloon League and Innovation in Politics” American Quarterly 32:1 (Spring 1980) 37-53.

Kerr, K. Austin. Organized for Prohibition: A New History of the Anti-Saloon League. (New Haven: Yale, 1985)

Kyvig, David. Repealing National Prohibition (2d ed). (Kent: Kent State, 2000).

Lamme, Margot Opdycke. “Tapping into War: Leveraging World War I in to Drive for a Dry Nation” American Journalism. 21(4) 63-91.

Link, William A. The Paradox of Southern Progressivism, 1880-1930. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992).

Merz, Charles. The Dry Decade. (Seattle: University of Washington, 1970).

Mills, Eric. Chesapeake Rumrunners of the Roaring Twenties. (Tidewater Publishers, 2000).

Moger, Allen. “The Rift on Virginia Democracy in 1896” The Journal of Southern History. August 1938 ( 4:3) 295-317.

Morris, Danny and Jeff Johnson. Richmond Beers: A Directory of the Breweries and Bottles of Richmond, Virginia. 2d edition. (Richmond: privately printed, 2000).

Morton, Richard L. History of Virginia. Volume III: Virginia Since 1861. (Chicago: AHA, 1924).

Odegard, Peter. Pressure Politics: The Story of the Anti-Saloon League. (New York: Columbia University, 1928).

Ownby, Ted. Subduing Satan: Religion, Recreation, and Manhood in the Rural South, 1865-1920. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990).

Parker, Alison M. “’Hearts Uplifted and Minds Refreshed:’ The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and the Production of Pure Culture in the United States, 1880-1930.” Journal of Woman’s History. 11:2 (Summer 1999) 135-158.

Pearson, C.C. and J. Edwin Hendricks. Liquor and Anti-Liquor in Virginia, 1619-1919. (Durham, Duke University Press, 1967).

Pegram, Thomas R. “Temperance Politics and Regional Political Culture: The Anti-Saloon League in Maryland and the South, 1907-1915” The Journal of Southern History. 63:1 (February 1997) 57-90.

Syzmanski, Ann-Marie. “Beyond Parochialism: Southern Progressivism, Prohibition, and State-Building” The Journal of Southern History. 69:1 (February 2003) 107-136.

Syzmanski, Ann-Marie. Pathways to Prohibition: Radical, Moderates, and Social Movement Outcomes. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003).

Thompson, Rev. S. H. The Life of John R. Moffett. (Salem, Virginia, privately published, 1895).

Van Wieren, Dale P. American Breweries II. (West Point, PA: East Coast Breweriana Association, 1995).

Wallerstein, Morton L., editor. Liquor Laws of Virginia: Including Federal Laws Relating to Interstate Shipments. (Richmond: Office of the Attorney General of Virginia, 1916).

Press

Alexandria Gazette

The [Richmond] Times-Dispatch

[Washington] Evening Star

Washington Post