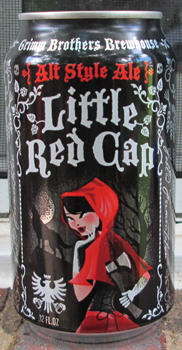

Little Red Cap: 2014

|

|

|

This month's can is Little Red Cap. I picked this design because the image on the label happens to fit some research I've been doing on brewery advertising in the late 19th and early 20th century and efforts to make beer and ale "family-friendly" beverages in the teeth of the prohibitionists' campaigns to portray all alcohol as threats to a health family. Little Red Cap is an alternate name for the more familiar Little Red Riding Hood, who is related to the traditional German Münchner Kindl. So what the heck does this month's can have to do with brewers' attempts a century ago to stave off the threat of the Anti-Saloon League and the Woman's Christian Temperance Union?

Making Beer "Family-Friendly"

(Note: some of the material focusing on pre-prohibiton advertising is from a paper I delivered at the 2014 American Historical Association meeting. Titled, “Liquid Bread: Brewery Advertising Countering the Prohibition Campaign, 1900-1920” I am reworking and expanding the paper for submission for publication. )

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, brewers unsuccessfully attempted to spare beer from the Prohibitionists’ ire by redefining alcoholic malt beverages as family-friendly temperance drinks, or even “liquid bread.” These efforts, however, had to overcome too many obstacles to succeed. Beer and ales were too firmly rooted in a male-dominated saloon culture to be redefined as appropriate for a respectable family dinner table. The liquid bread campaign simply ran directly counter to the brewing industry’s traditional advertising themes and customer base.

At the start of the 20th century, about 90% of all beer was sold on draught, most commonly consumed on the premises at saloons, and a large portion of bottled beer was consumed not at home, but in restaurants. This reliance on the saloon lay at the heart of the breweries’ problem. Saloons were the center of male drinking culture and of the vices associated with it.

Women were admitted into saloons under particular constraints and with pre-specified roles. Prostitutes were permitted to frequent some saloons, although they not always welcome, harassed even if they were allowed to remain. Other establishments had a “Ladies’ Entrance” to one side. A woman could enter this side door, often into an anteroom physically separate from the rest of the bar, and buy beer to take with her. Thus female customers could be served, while still maintaining the segregated male preserve that was the business’s bulwark.

Children had an even more limited access to saloons. The most common place for children was that of a helper, cleaning or running errands for the saloon-keeper or his patrons. “Rushing the growler” or running to fill pales of beer for workers and families for a penny was a common way for some boys in urban areas to make money. An enterprising, and strong, boy might carry numerous growlers along a shoulder pole to serve multiple customers simultaneously.

In contrast to the saloon stood the traditional German beer garden, which was intended for families, a direct contrast to the saloon’s male-only space. Carried over from the middle-European tradition mainly by German-speaking immigrants, beer gardens were usually set outside, where families could sit and enjoy pleasant weather while listening to popular music, while the adults drank beer. The beer garden presented an alternative to the saloon, but, outnumbered by the non-family-oriented saloon, the beer garden was never accepted by much of the American public as a realistic alternative.

While saloons were male-centered, the temperance campaigns centered much of their argument on women and children. Intoxicating beverages were a threat to wives, children, to everything about the home. Prohibitionists commonly used images of children, imploring voters to vote to close saloons for the children, “The Saloon, or the Boys and Girls.” Images of families impoverished by a father that drank were a common part of temperance campaigns throughout the 19th century and beyond. Children were also used not just as symbols, or even spokesmen, but as future recruits. They signed pledges to abstain as adults from alcohol (and often, tobacco as well) with the slogan, “Tremble King Alcohol, We Shall Grow Up!”

The brewers’ response followed several tracks. First, they tried to convince the public that beer was a healthy beverage. They also worked to separate the beer industry from that making distilled liquors, portraying beer as a “temperance beverage.” Finally, they attempted to make beer a family-friendly product by showing its consumption in family-friendly settings.

|

| 1906 ad with family. |

These efforts had numerous obstacles to overcome, not the least of which was the established types of beer advertising then commonly in use. The breweries still had to market to their traditional customers, men consuming beer outside the home in male-oriented saloons. Women appeared in many beer advertisements and on numerous labels, but most commonly as objects of sexual desire for male consumers, sometimes blatantly, sometimes more subtly.

|

| Buffalo Beer Tray. From the Trayman site. (I emailed and asked permission to use, but never got an answer. I'd appreciate it if the site owner emailed me. It's a great site! |

Children rarely appeared by themselves in brewery ads. That's not unexpected as beer was considered an adult beverage. There are a few exceptions. Brewery advertising sometimes showed children sitting at a dinner table in a family setting where the adults are consuming the beer being advertised. In this case the children were presented in a stable, middle-class environment. These images were generally limited to print ads, most commonly in newspapers. The other two examples are children in pre-pro beer advertising were mythical, or folkloric figures.

|

| 1911 Peter Doelger Ad. |

The first was cherub-like figures. However, these represented mythical figures, rather than realistic. Another popular figure was a small girl, often holding a beer stein, and wearing a cloak. Although the figure was used by several breweries, it was probably most commonly used by Detroit’s Stroh Brewery, and is clearly based upon the traditional Münchner Kindl. Originally a small monk, the figure evolved until by the late 19th century she was usually portrayed as a small girl wearing a black cloak with yellow stripes. In the US version, however, she wears a red peaked cloak, looking like Little Red Riding Hood. Not coincidentally, Little Red Riding Hood was a popular, well-known figure in Kirch in the Palatine region of Germany, where the Stroh family originated. And Stroh’s ads like to mix the two: the red cloak and hood with the stein or barrel of beer. In this guise, the little Münchner Kindl girl blurred the distinction between mythical and realistic. She was both non-threatening and non-sexual, although Strohs did sometimes combine the little girl with a more traditional sexualized adult image such as the little girl delivering a case of Strohs Beer to a pretty young adult woman. So there is likely a connection between the Münchner Kindl and Little Red Riding Hood. And yes, Little Red Cap is another name for Little Red Riding Hood.

|

| Here is a detail of a Münchner Kindl from a postcard. Click the image to see the entire card. |

Little Red Riding Hood

In the original story, Little Red Riding Hood (LRRH) does not wear a red cap or cape, but she is taking food to her grandmother. A werewolf stops her and asks where she is going. The rest sounds like the familiar story, LRRH takes one path, the wolf another. The wolf gets to Grandmas's house first and devours her. The older European versions have additional details missing from the modern American story. For example, the wolf asks what path LRRH will take, the Path of Needles, or the Path of Pins? LRRH says she'll take the Path of Pins so the wolf takes the Path of Needles. We'll get to what this means in a moment. Also, in one gruesome detail, the wolf saved some of the grandmother's blood and flesh and serves them to LRRH. Ew.

The wolf takes the place of the now eaten grandmother in the bed and tries to fool LRRH. "What big ears you have!" "The better to hear you with" etc. LLRH catches on that something is wrong and after the wolf has gotten her to undress and climb into bed to keep warm, LRRH says she has to relieve herself, so she goes outside. Instead she runs away and the wolf gives chase. LRRH comes across some women doing laundry in the river and they hold a sheet across the water so she can cross to safety. When the wolf appears they do the same, but snatch the sheet away, letting the wolf drown.

Much of the familiar version we know comes from French variants on the story. Some of them have the needles and pins part. This probably reflected the fact that sewing and spinning were a familiar parts of women's duties, often done communally. Young girls reaching puberty would often be sent to live with a seamstress to learn sewing. This necessarily involved learning how to dress as an adult. Once they finished this training, the young women would enter a new stage in the community, where they could court and have sweethearts. Boys could give pins as presents to girls they liked as a present. So "taking the Path of Pins" would signify that the young woman was just entering puberty.

Needles, on the other hand, had a sexual connotation (think of the thread hole). Prostitutes sometimes used the needle as a symbol to advertise their profession. (Terry Pratchett fans will recognize the Seamstress Guild here). In a version where LRRH took the Path of Needles it could indicate that she was trying to grow up too fast, to become sexually mature too quickly. In the version where LRRH took the Path of Pins, the wolf took the Path of Needles--he was a sexual predator. Of course the idea of the wolf as a sexual predator is not exactly unknown, as seen in countless 20th century cartoons. Moreover, in many version the wolf has LRRH do what is basically a striptease (take off your cloak, take off your stocking, etc) so the sexual imagery is very much out in the open.

French author Charles Perrault (1628-1703) modified many traditional folk tale into forms that are more familiar today. Written for the French Court to enjoy, LRRH's encounter with a wolf trying to get her to climb into bed with him was a barely disguised warning to young women entering court society to beware older male sexual predators. In his version of the story LRRH does wear a red cap, which was a bit gaudy. Young and naive she stops to pick flowers and watch butterflies, allowing the wolf to get the grandma's house first. Perrault skips the cannibalism and striptease, but in the end LRRH gets eaten, the end. Sorry, no happy ending here. It was the Brothers Grimm's version that introduced a hunter to save the day. He cut open the wolf's stomach, freeing LRRH and her grandmother. Then the hunter fills the wolf's stomach with stones, killing him.

The wolf is also an interesting part of this story. Allegorical monsters were common in pre-modern European zoology. Descriptions and illustrations would be published in popular "Bestiaries." Such monsters would commonly be based upon existing dangerous animals from the region, so wolf-based monsters would make sense for much of Europe. The wolf was a known threat, so it made a handy template for monsters.

|

| Gustave Doré's engraving of the scene:"She was astonished to see how her grandmother looked" Wikipedia. Circa 1880. |

The version most Americans know comes from a blending of the French and German tales that were popularized in Britain and the US. LRRH is often a little girl in these versions, removing the blatant sexual predator aspect, and she is often saved by a hunter or woodsman. In the mid-twentieth century the story was frequently modified and retold. LRRH sometimes became an older, sexually aware young woman. In others she was still a young girl, but streetwise and wise-cracking. In version where she is younger the story's focus tends to be on her disobedience, such as taking too long to go to grandma's house, and talking to strange wolves. In versions where she is older, the stories are more orientated towards danger from an older, sexually experienced male. In both cases, she likely to be able to defend herself without the help of a nearby man.

|

|

| Two different versions from the first half of the 20th century. The one on the left is from 1927. The one on the right is a Works Progress Administration poster by Kenneth Whitley, 1939. Wikipedia. | |

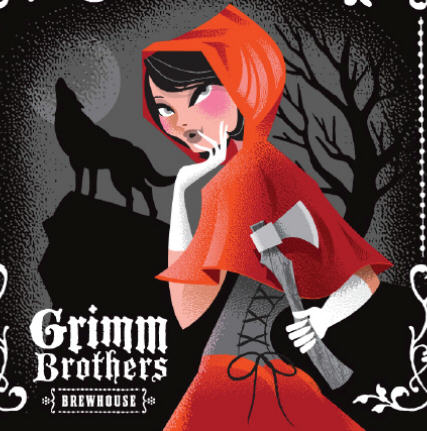

This month's can fits the more modern version. Little Red Cap is clearly a grown woman as indicated by her clothes, which emphasize her figure, and her face, which has makeup. She's smiling at the viewer with her hand held up to her face as if to teasingly say "oh my, what will I do?" And she's got an axe hidden behind her back, so she's quite able to defend herself against the howling wolf in the background. Of course a wolf howling has its own sexual meaning as well. The full moon works well with the wolf image, as well as with the werewolf in the original story. In addition, the full moon is often associated with madness and personal license, including sexual misbehavior. We won't dwell on the axe and male castration fears.

|

So where does this leave us? Breweries began using children in their ads in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, in part to assure consumers that their product was pure and wholesome. One of the most common images they used was the Münchner Kindl, which itself was related to Little Red Riding Hood, at least in America. That folktale had its own historical meaning about purity and childhood, so it seems fitting that it intersected with the brewing industry campaign. And this month's can has brought the story full circle, with a sexually mature LRRH selling beer.

The Grimm Brothers Brewhouse

This month's can is from a Loveland, Colorado brewery, Grimm Brothers. Their website notes that it was "founded by avid homebrewers captivated by the rich tradition of European beers. They knew that the long history of beer production in Germany and surrounding areas would give them plenty of tales to share with their customers. Inspired by the stories collected By Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, they have crafted their beers to tell not only the story of Craft Brewing, but the harrowing and dark tales handed down through the generations."

Their beers definitely have a folklore/fairytale theme. Besides "Little Red Cap" they also produce "3 Golden Hairs", "The Fearless Youth", Master Thief", and "Snow Drop" which has a Snow White-themed label. Visit their site to learn more. But as a historian who likes reading about folklore, I definitely approve of the take their labels have on the traditional stories.

Sources:

Links each open a new page.

A retired University of Pittsburgh professor, D.L. Ashlimann, has a nice page of links to Little Red Riding Hood/Little Red Cap variations.

One of the variations of the story: "Little Red Cap"

Stephen T. Asma. On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears. (2009)

Terri Windling. "The Path of Needles or Pins: Little Red Riding Hood"